Lusofonia, a (R)Evolução: Discourses of Atlantic Roots and Routes in «Luso World Music»

This article presents the development of a «Luso world music» (La Barre 2010), a transnational musical movement bringing together popular and traditional musics of the Portuguese-speaking world and departing mainly from the city of Lisbon. Special attention is given to the documentary Lusofonia, a (R)Evolução, produced by the Portuguese delegation of the Red Bull Music Academy in 2006, and the documentary’s impact on this movement. The article shows how the idea of «lusofonia» as a discursive concept is used by culture politics in Portugal today and how discourses of Atlantic roots and routes in lusophone popular music are presented in the documentary.

After ten months of production, the documentary Lusofonia, a (R)Evolução,1 hence forth Lusofonia, was shown for the first time to the public in Lisbon on 26 October 2006 at the 4th DocLisboa.2 3 The screening was followed by a party including performances of migrant musicians from Portuguese-speaking countries at Lisbon’s «B.Leza» bar. The event served to raise funds for the Lisbon-based cultural association Khapaz that promotes young musicians of African descent in Portugal. Throughout November 2006, Lusofonia was screened for free at FNAC shopping malls4 in Lisbon, Porto and Coimbra. Throughout 2007 it was broadcast on Portuguese radio and television (RTP)5 and on MTV Portugal. The trailer with English subtitles, segments of the documentary and recently the whole documentary can be accessed on YouTube (accessed 11 November 2013).

According to Bart Vanspauwen (2010, 40), the film has also been offered to festivals outside Portugal through the global network of the multinational Red Bull Music Academy (RBMA). In fact, the incentive for the production of this documentary has been taken by representatives of the Portuguese delegation of the RBMA.6 Lusofonia, however, did not result from an RBMA in Lisbon.

The script of Lusofonia was written by Arturo Soares da Silva and João Xavier, and its executive producer was Mariana Moore Matos. As Matos is responsible for the media office of the Portuguese Red Bull Music Academy, it was her whom I contacted to get a copy of the documentary, at a time before one could find it on YouTube. The documentary has not had commercial distribution and was at first only available as a promotional dvd+cd pack edition, accompanied by an online press kit (N.N. 2006, hence forth press kit).

The main promotion platform has up to today been Myspace (accessed 11 November 2013). Financially and institutionally the documentary was supported by RTP, the Instituto Camões, the Municipality of Lisbon, and the Comunidade dos Países de Língua Portuguesa [Community of Portuguese-speaking Countries] or «CPLP».7

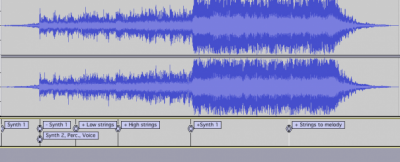

Lusofonia traces the development of a «música lusófona» («lusophone music», Vanspauwen 2010, 59) or «Luso world music» (La Barre 2010), a transnational musical movement bringing together popular and traditional musics of the Portuguese-speaking world and departing mainly from the city of Lisbon. The aim of the film was to document a lusophone musical identity emerging from Portuguese colonisation since the fifteenth century, to give a glimpse of the sound of the Portuguese-speaking world today, to promote the concept of fusion between Portugal, Brazil and the Portuguese-speaking African countries (referred to as PALOP) and ultimately attract institutional and commercial support for these musics. Curiously, the documentary focuses on musicians already promoted by established labels, while performance practice at the grass roots level and public reception of «Luso world music» are not represented (Vanspauwen 2010, 46). It includes thirty-five interviewees,8 thirty-three bands, music videos9 and bibliographical research.10

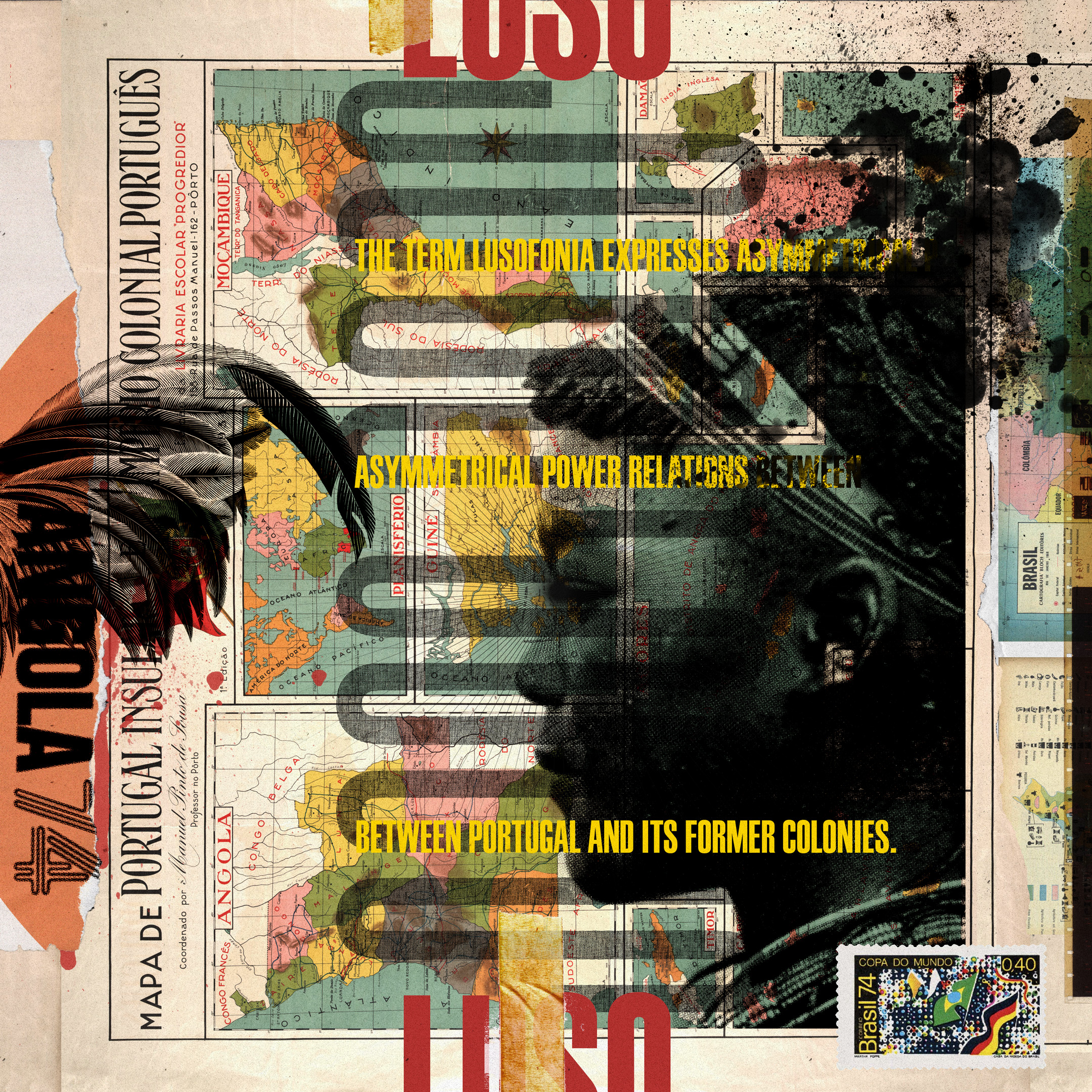

In this text I argue that the documentary Lusofonia, a (R)Evolução is mainly informed by the idea of lusofonia (lusophony),11 a discursive concept expressing the brotherhood of Portuguese-speaking countries and representing the Portuguese language as a sort of «blood bond» between Portugal and its colonies.12 The Portuguese-speaking world embraces around 220 million speakers on five continents; Portuguese is the official language in Angola, Mozambique, Brazil, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Portugal, São Tomé and Príncipe and East-Timor. However lusofonia is not just a linguistic, but also a political, economical and cultural space.

The documentary professes that a bond among the different Portuguese-speaking countries is also expressed musically. «Portugal», states one of the documentary’s interviewees, «has always been acquainted with Brazilian music […] and Cape Verdean rhythms as well as semba and kuduro from Angola have already for a long time been part of Portugal’s soundscape». (Francisco Rebelo, João Gomes and Tiago Santos, members of the band Cool Hipnoise, in Soares da Silva, Xavier and Matos 2006). The viewer then learns that this exchange of sounds from different Portuguese speaking countries is also reflected in Lisbon’s nightlife. According to music journalist David Ferreira interviewed in the documentary, «the approximation of different cultures is what gives Lisbon, respectively Portugal, its identity» (in ibid)). However, what Lusofonia criticises is that Portuguese media and culture politics have so far not paid enough attention to the phenomenon of transnational Portuguese popular music and that world music from Portuguese-speaking countries has mostly been produced by record labels outside Portugal, such as World Connection in Haarlem (Netherlands) and Lusáfrica in Paris.13 The documentary aims to awaken Portuguese cultural entities, radio and TV stations and the ministry of cultural affairs to the commercial potential lying in the Lisbon music movement that «radiates some unique traits: whether they be rhythms, melodies, or words which epitomize, by way of sounds, five centuries of joint history in the territories which today share the Portuguese language» (press kit 2006, 4).

The following text is a meta-commentary on the English-language version of the press kit accompanying Lusofonia, a (R)Evolução. It is divided into the five chapters of the documentary that follow in a chronological order important moments of Portuguese history: the colonisation in the fifteenth century (chapter «At the Roots of this Fusion»), revolutions in the 1970s (chapter «Song as a Weapon»), Portugal’s internationalization in the 1980s (chapter «The 1980s Boom»), the growing importance of lusofonia as a political concept in the 1990s (chapter «The New Multiculturalism») and the emergence of a new multiculturalism in the twenty-first century (chapter «Sound (R)Evolution»).

At the Roots of this Fusion: Colonisation and Fado

It all began in the 15th century, when Portugal embarked on its maritime expansion. A small country of around one million inhabitants travelled across the Atlantic and reached Brazil, ventured round Africa and Asia – of India, Japan or Indonesia. It wrought an empire, one of the foundations of which lay on the slave trade. This dark side of history (present from the empires of Antiquity up to the present age) created in Portugal a community of Africans who brought their customs, rituals, music and dances with them to Lisbon. Around the 1450s, 10% of the population of Lisbon was of African origin. With the passage of time, the miscegenation between blacks and whites gave birth to multicultural people – it’s not by chance that Brazil is the most multicultural country in the world. Against such a background, music and dancing were elements of integration. Several types of music evolved throughout the centuries, the most popular of which being Fado – firstly a dance, then a song, its roots pointing towards multicultural blending, as put forward by José Ramos Tinhorão in his book Os Negros em Portugal: Uma Presença Silenciosa (1994). (press kit 2006, 2)

Theories on the origin of fado such as those of José Tinhorão (1988) and Rui Nery (2004) assume that fado first was a dance in Brazil and later a vocal genre in Lisbon. In its earliest forms in Brazil at the end of the eighteenth century it is said to have been a fusion of the African derived dances fofa and lundum with the Iberian fandango dance. Regarding its emotional ingredient, fado was probably inspired by the vocal genre of the modinha, which was popular in Brazil and Portugal in the eighteenth century. Fado as a vocal genre only emerged in Lisbon after 1820 (Nery 2004). Today, fado can be categorized as a Portuguese urban song genre that is performed in the whole of Portugal.

Despite theories that implicate fado as a result of cultural encounters in nineteenth century Brazil, Lusofonia stresses that already by the fifteenth century music and dance of different cultures were integrated in Portugal. It purports that fado is a mixture of the dances fofa and lundum, which emerged in Lisbon during the fifteenth century, and was then brought to Cape Verde and Brazil where slaves sang of their suffering. From there consequently the musical genres morna (Cape Verde), seresta and samba canção (both Brazil) emerged. Cape Verdean singer Celina Pereira states in the documentary that fado and morna have certain emotions in common through which Portuguese and Cape Verdeans recognize each other, the most important being the feeling of saudade (longing).14

Themes such as «seafaring, deterritorialization and melancholy» play a big role in fado. And, as Kimberly da Costa Holton further observes: «What is amazing, is not only the projection of fado’s fifteenth century genesis, an idea now long debunked by fado historians, but also the way in which discovery-era navigators serve [in fado] as the metonymic extension of twentieth century soldiers who fought in the colonial wars» (Holton 2006:3). The colonial wars in the Portuguese space are also the theme of the next chapter of Lusofonia, a (R)Evolução.

Song as a Weapon: Protest Song in Portugal, Angola and Brazil in the 1970s

In the 20th century, music in the Lusophone sphere took on a role of protest against dictatorial regimes. Symbolic of which is the 25th April Revolution in Portugal – the revolution which started with a song. The country underwent a revolutionary period and protest music took on a seminal role in the shaping of consciences and the changing of attitudes. The same happened in Africa and in Brazil. In the aftermath of the revolution, José Afonso, José Mário Branco and Sérgio Godinho used the Portuguese language to fight for change, and in the African countries, both the language and the music from Portugal (and in certain cases its Creole offshoots) has assumed their protest character by the hand of Rui Mingas, Super Mama Djombo and Bonga. Between Portugal and the Lusophone countries, music was both a fraternal bridge and a point of union. In the aftermath of the revolution, both Africans and Portuguese migrants returned hastily to Portugal, bringing with them a musical seed which would explode years later (press kit 2006, 2).

The documentary shows how music served as a tool for social intervention in the decolonization of Africa and in the resistance against dictatorships in Portugal and Brazil. In 1961, the national resistance movement, which had started in the 1950s, led to a liberation war in Angola. Only as a consequence of the military coup in Portugal on 25th April 1974 the liberation war in Angola came to an end, and in 1975 Angola gained its independence. The military coup in Portugal, also known as «Carnation Revolution», brought down the dictatorial regime of the Estado Novo (New State) that had ruled Portugal since 1926. The new democratic government in Portugal immediately began decolonization in all lusophone African states. In the course of each country gaining independence, 700,000 Portuguese living in Africa as emigrants or soldiers, the so-called retornados (returned), returned to Portugal. They brought with them sounds from Africa, which, according to the documentary, also «shaped the music of Portugal». Thus, the documentary implies, the concept of lusofonia gained importance in the 1970s with musicians from Portuguese-speaking countries arriving and settling in Portugal.

In the late period of Portuguese colonial rule, European and Brazilian musical productions dominated the music scene in the Angolan capital Luanda, while Congo and Zaire were more influenced by Cuban music. Santoca (Sebastião Vicente, b.1954, Luanda) and Mário Rui Silva (b.1952, Luanda) belong to the young generation of Angolan musicians who sang for the independence of their country in Portuguese and Kimbundu.15 The Angolan group Duo Ouro Negro (f.1956) together with Angolan singer-songwriter Bonga (b.1943) were among the first musical groups to mix Angolan and Portuguese traditional music and they became popular in Portugal after the Carnation Revolution. As a consequence of increasing diplomatic relations between Angola and the Netherlands, these musicians were by-and-large produced in the Netherlands, where Bonga was also exiled from Angola in 1972. In Europe, Bonga encountered other Portuguese-speaking musicians and incorporated elements of Brazilian samba into his diverse musical style. After the Carnation Revolution, Bonga moved to Lisbon, and also lived some time in Paris and Angola.

Brazil was ruled by the Estado Novo (New State) regime between 1938 and 1945, and by a military regime between 1964 and 1985. The Brazilian movement of the Tropicália (1967–1969) aimed to create an identity in opposition to the military regime. The movement also found its reflection in music, in that Brazilian popular music was hybridized and internationalized. Tropicália combined Brazilian music with international popular music, primarily pop and rock. At the centre of the movement stood the African diaspora in Brazil, in particular traditional music from the Brazilian North-East. As a musical phenomenon, Tropicália cannot be classified according to style or rhythm. Rather, its focus is the expression of political and existential crises of left-oriented urban artists and intellectuals who identified with the liberal movement of the United States, with the New Left (Party), American university life, the new experimental literature and theatre, drugs, as well as the Black Power movement in the United States.

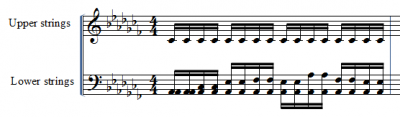

In Portugal, political song from the 1940s to the 1970s provided a platform for expressing opposition to the Estado Novo regime. In the course of the 1974 revolution, political song became interventional in nature, and was characterised by literary texts, simple rhythms and harmonies and guitar accompaniment (sometimes also piano and traditional Portuguese instruments). The most famous Portuguese protest singer is José (Zeca) Afonso (1929-1978) who produced his album Cantigas do Maio (Songs of May) in 1971 in Paris. Other singers include Fausto Bordalo Dias (b.1948), Vitorino (b.1942) and his brother Janita Salomé (b.1947). The protest singers Luís Cilia (b.1943, Angola), José Mário Branco (b.1942), Francisco Fanhais (b.1941) and Sérgio Godinho (b.1945) returned from their exile in France to Portugal in 1974. Next to traditional Portuguese music, the popular French song and African and Brazilian popular music influenced the political song in Portugal. While fado stood for the ideas of the regime and was disseminated officially, the political song was disseminated unofficially, mostly via radio. Inspired by revolutionary ideas, students from Lisbon, Coimbra and Porto collected traditional Portuguese music at the end of the 1970s. They were inspired by ideas of Portuguese composer Fernando Lopes-Graça (1906–1994) and music researcher Michel Giacometti (1929–1990), who had collected mainly traditional vocal music from Portugal in the 1960s. Between 1975 and 1985, folk revival groups were active in Portugal. They were often composed of up to twelve members and used traditional instruments from one or more regions of Portugal. While some groups, such as for example Almanaque, championed the authenticity of traditional music using traditional instrumentation and respecting the accent of the Portuguese regions from which the songs were taken, other groups, such as Brigada Vitor Jara, changed the traditional instrumentation and mixed traditional Portuguese instruments with non-traditional instruments, introducing new harmonies, rhythmical schemata and melodic fragments in the accompaniment.

Lusofonia includes the song «Milho Verde» from the Portuguese region of Beira Baixa performed by José Afonso in the Coliseu in Lisbon in 1983.

In the context of this performance, José Afonso mentioned that this song blended rhythms from the square tambourine adufe used in Beira Baixa with African rhythms, and that «many similarities between songs from Beira and African rhythms, especially those from Angola» (transcribed from the English subtitles of the documentary) exist. In the 1960s collaboration between musicians from lusophone Africa and from Portugal happened especially «in the domain of música popular portuguesa [popular urban song], the canção de intervenção [intervention song] and performers and composers with biographical links to African countries, such as José Afonso (Angola and Mozambique), Fausto (Angola) and, later, João Afonso (Mozambique)» (Cidra quoted in Vanspauwen 2010, 17f.; my translation).

The 1980s Boom: Rock16 and Internationalisation

During the 1980s, collective work between musicians was reinforced. Paulo de Carvalho, José Afonso, Rão Kyao, Heróis do Mar, Tito Paris or Danny Silva are a few of the examples. The attempts of the artistic community to assume the Lusophone trait in their work lived side-by-side with the emergence and the assertion of a generation by way of Portuguese rock music (first half of the 1980s) and the birth of electronic music (late 1980s, early 1990s). Nevertheless, these movements of musical blending were not accompanied by the societies and integration policies. (press kit 2006, 2f.)

While the 1970s were shaped by the aftermath of the revolution and decolonisation, Portugal opened up to the international popular music market in the 1980s. In 1986 Portugal joined the European Union. Portugal’s generation born in the eighties wanted to break with the ideology of the past and become cosmopolitan, despite that working conditions were poor and that musical instruments and equipment were hard to come by. New popular music groups swamped the lusophone space. In Portugal groups like Táxi, Heróis do Mar, Pop dell’Arte and Sétima Legião as well as the experimental musician António Variações (1944–1984) were active. In Angola, the orchestra «Semba Tropical» was founded in order to fill a gap in music production caused by the colonial war. Although musicians from lusophone Africa performed in Portugal in the 1980s, collaboration between musicians from different Portuguese-speaking countries did not happen.

The New Multiculturalism: Electro and the Politics of Lusofonia

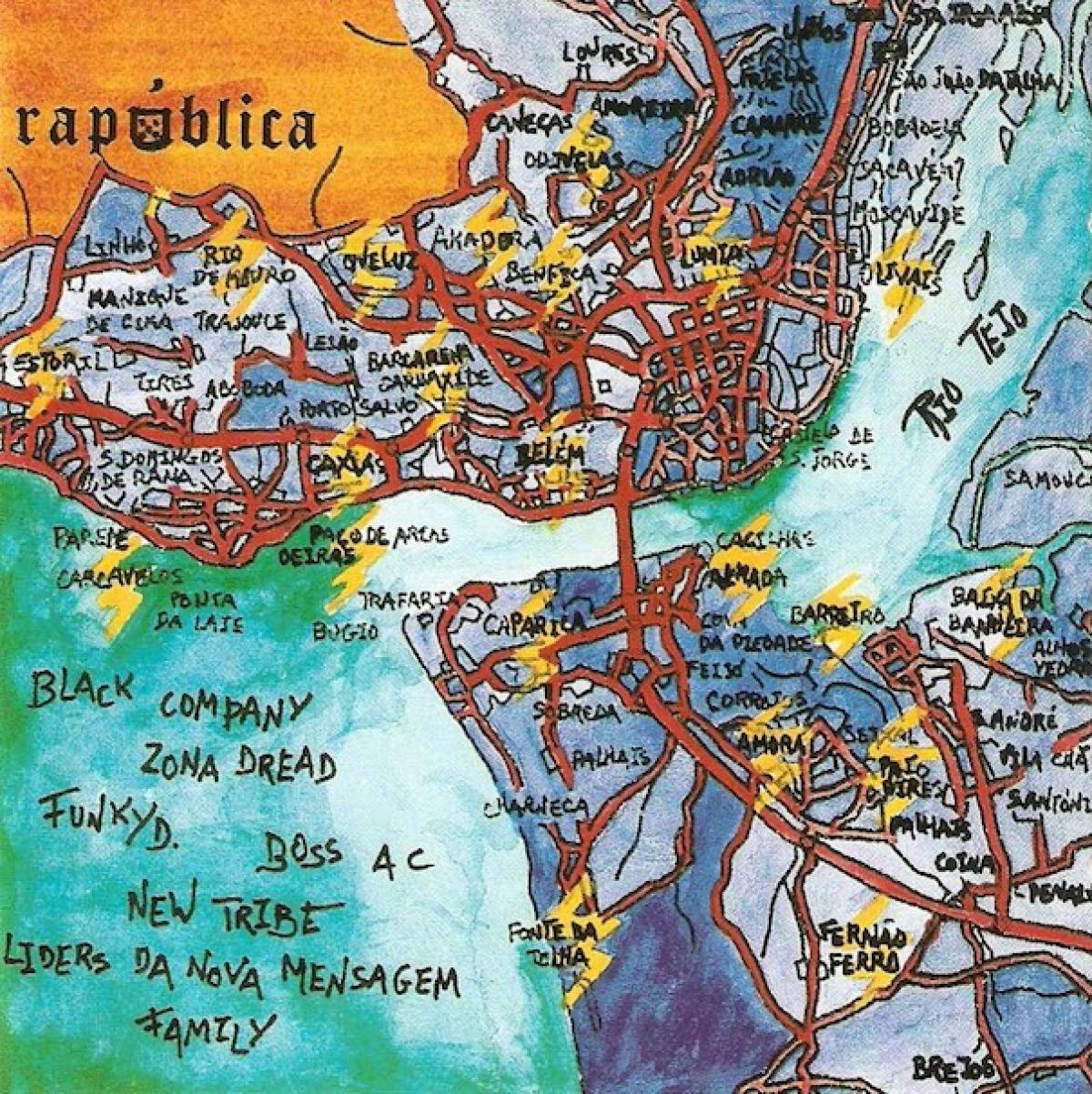

But with the emergence of electronic music a new chapter was written. In the beginning of the 1990s, the country witnessed the arrival of a new culture brought on by electronic compositions, with Hip Hop as a driving force. In this decade, the descendents of Africa and second-generation migrants acquainted themselves with this culture, substantiated by releases such as «Rapública». The 1990s, with electronic music as a driving force, revealed a Portugal in which the Lusophone trait was expressed through the aesthetics of dance music. The Portuguese language formed a global wave through genres such as House and Nu-Jazz, by way of Brazil; remixes of Cesária Évora were a success, and hailed as innovative projects. (press kit 2006, 3)

According to the opening statement in this chapter of the documentary, the idea of lusofonia was revitalised in the 1990s and «just as in the fifteenth century, music became an element of integration once more» (transcribed from the English subtitles of the documentary; Soares da Silva, Xavier and Matos 2006). The growing shared interests of political institutions and cultural promoters encouraged interaction between musicians from different lusophone countries, especially in the domains of jazz and música popular portuguesa (popular urban song). Such collaboration was reflected in the festival Sons da Fala in Galicia (Spain) in 1994 and in the foundation of the Orquestra Sons da Lusofonia in Lisbon in 1995. Brazilian musicians, however, did not figure in either of these projects (Vanspauwen 2010, 18).

The revitalisation of lusofonia owed much to the new multiculturalism of a generation of urban, hip-hop influenced musicians born of Portuguese-speaking migrant parents. In 1994, a compilation released by the group Rapública is noted as the first Portuguese rap album. «The idea of lusofonia, emerging by way of Rapública, thus originally focused on the potential of lyrics in the Portuguese language» (Vanspauwen 2010, 42). The concept of lusofonia has up to today musically also been realized in cultural institutions and bars such as the Casa do Brasil (f.1992) and B.Leza (f.1995) in Lisbon, and promoted via radio and television stations such as RDP África (f.1995) and RTP África (f.1998) in Portugal, the Afro Music Channel based in Lisbon and Madrid, and Radio Lusofonia in Johannesburg (ibid., 30f).

In 1996, the concept of lusofonia was institutionalized in the CPLP. A special place for lusofonia was reserved two years later in the World Exposition (Expo ’98) taking place in Lisbon, which alluded discursively to Portugal’s maritime expansion and the cultural marks it globally imprinted under the theme «The Oceans, a Heritage for the Future». Musicians from different lusophone countries came together in the context of Expo ‘98, whereby Brazil was the country musically most represented. Unprecedented musical collaborations among popular musicians from the lusophone space happened in the Expo ‘98’s project Sem Legendas (ibid., 20). According to Timothy Sieber, however, little «lusophone music» was presented in Expo ’98 and it was separated from «Portuguese music» which was presented as a homogenous European national culture, mainly represented through fado and jazz and to a much smaller extent through institutionalized groups of traditional music and dance, so called ranchos folclóricos. The event conveyed the impression that Portugal’s influence on other cultures was stronger than those of other cultures on Portugal (Sieber 2002, 168). According to Carlos Martins, leader of the orchestra Sons da Lusofonia, the exhibition showed «a little music of Cape Verde, a little dance of Goa, a little food in a cafe […] this was the image of Lusophonia they were giving, but it was not enough» (quoted in ibid., 180). Sieber further informs: «The only immigrant groups or individuals in the Portuguese category [in Expo ‘98] were a few, second generation, Portuguese-born singers of African descent, mostly hip hop-artists such as Black Company and General D.» (ibid., 173), and they tended to sing more in a Western than in an African style. As a result of Expo ‘98’s project Sem Legendas, the CD Onda Sonora: Red Hot + Lisbon (Dranoff and Levin 1998) was then produced in New York under the curatorship of David Byrne.17 This production aimed at unifying rhythms, melodies and songs of all Portuguese world cultures in one recording. However, according to Timothy Sieber the production included only a few tracks of migrants from the lusophone world in Portugal, among them Lura (Cape Verde/Lisbon), Bonga (Angola/Lisbon) and General D (Mozambique/Lisbon).

Sieber describes the lusophone fusions on this album as «mostly studio-created, artificial constructs that had little actual presence in the Portuguese capital» (2002, 178) and quotes music critic João Lisboa:

Onda Sonora / Red Hot + Lisbon is founded in a great project of wishful thinking –imagining Lisbon as a multicultural and cosmopolitan European capital, a magnet for world musicians (like Paris or London are, for example) where from the African ex-colonies to Brazil and even Asia an immense cultural stew is boiling, and the roots of the world’s diverse traditions cross and combine in a festive celebration of differences and identities. [...] pretty far from the truth [...] this album has in fact little to do with the capital and its peripheral countries as they really exist. (Lisboa quoted in ibid., 179)

Lusofonia does not mention these musical projects from the 1990s. The documentary emphasizes more the lusophone trait manifested in the aesthetics of electronic dance music and the use of Portuguese language in House, Nu Jazz, and re-mixes. In Portugal, according to the documentary, it was mainly the group Rapública bringing black and white musicians together, while the Portuguese reggae band Kussondulola acquainted the young audience with African music. The documentary also mentions that music and rhythms from Cape Verde, such as funana, and from Angola, such as semba, kizomba and kuduro have been part of Portugal’s soundscape since the 1990s. It gives special attention to kuduro saying that in Angola this electronic dance music was used for intervention, and was also produced in Portugal by the band Buraka Som Sistema. Music critic Vítor Belanciano states in the documentary that kuduro could even be Portugal’s Grime or 2Step, arriving on the dance floors of the world (on kuduro see also Alisch and Siegert 2011, and Alisch 2013). The chapter «The New Multiculturalism» of the documentary also includes a performance of the band Spaceboys that mixes kuduro with funk and jazz and that is produced by the Portuguese label Nylon. Nylon is, together with Norte Sul, Enchufada and Loop, among the labels promoting popular music from the lusophone world. The only reference to Mozambique is made in the documentary’s chapter «The New Multiculturalism» by presenting Mozambican musician N’Du playing the drum and stating that African rhythms are reflected in Drum’n Bass.

Sound (R)Evolution: Pop and Multiculturalism

And it is at the beginning of the 21st century that we witness a generation in Portugal which synthesizes the whole legacy brought on since the 25 April 1974. A Lusophone streak is finally assumed in the creative sphere; a new wave is aware of the heritage of the past and affirms it as a distinctive trait. Hip Hop in Creole, dance music with samplings of Kuduro, Portuguese lyrics over contemporary structures. (press kit 2006, 3)

The mixing and blending of different elements of lusophone expressive culture with Western popular music continued after 2000. New musical hybrids emerged for example through the blending of samba with hip-hop in the case of Marcelo D2, through Cool Hipnoise’s different approach to Brazilian rhythms, through Kussundulola’s Angolan-inspired reggae and the vitality of Creole in music of Nigga Poison and Chullage (Vanspauwen 2010, 43).

According to Portuguese rapper Chullage (b.1977, of Cape Verdean descent), Capeverdean musical genres of morna and funana are today being brought into hip-hop while Angolans are discovering Brazilian samba and Cape Verdeans get to know Angolan semba. «The music from these countries is bringing us together», says Chullage, «we look at what is coming out of these countries and we are creating a common repository» (transcribed from the English subtitles of the documentary; Soares da Silva, Xavier, and Matos 2006).

The documentary stresses that «Brazilian music is the most visible facet of Lusophony on the world music market, but there are artists from other Portuguese-speaking countries which are working their way into the world music scene», referring mainly to musicians of Cape Verdean descent such as Cesária Évora (1941-2011, born in Mindelo, Cape Verde), Tcheka (b.1973, Santiago, Cape Verde), Lura (b.1975, Lisbon), and Sara Tavares (b.1987, Lisbon) (ibid.).

In the documentary Vítor Belanciano criticizes the fact that musicians from Cape Verde have so far mainly been promoted by international music labels such as World Connection in Haarlem (Netherlands) and Lusáfrica in Paris. The Portuguese recording industry, however, would not, according to Belanciano, invest in «what gives us an identity, us Lisbon, us Portugal, as a market in the convergence of several cultures, especially the Brazilian or the African» (transcribed from the English subtitles of the documentary; quoted in Soares da Silva, Xavier and Matos 2006). In the documentary José da Silva, editor of Lusáfrica, points out that unlike Portugal the francophone world has a good system for promoting world music and that «Cape Verde can make it, thanks to its foothold in the Francophone world» (da Silva in ibid.). According to fado singer Carlos do Carmo (b.1939, Lisbon), «we, the Portuguese have a difficulty in assimilating this as something to which we are connected: the natural synergies of history» (do Carmo in ibid.), and thinks that the French have less complexes towards their world music. Addressing his young lusophone colleagues, Carmo says that they stand for a new culture, a culture that must not only be respected, but heard in order to learn from it. His own fado resonates in the documentary in a Luso world music example par excellence, namely in a mix of rhythms from lusophone Africa and Brazil, fado samples and popular Western styles such as hip-hop or techno made by Portuguese rapper Sam the Kid (b.1979).

Conclusion

The documentary Lusofonia, a (R)Evolução legitimizes a Luso world music movement through Portugal’s colonial history and globalisation, selecting certain moments of this history such as the beginnings of colonisation in the fifteenth century, revolutions and decolonisation in the 1970s, the influence of internationalisation in the 1980s, the institutionalization of the concept of lusofonia in the 1990s and musical hybridization in the twenty-first century. It neither takes into account Portuguese migration after the fifteenth century, nor does it look closely at the dispersal of European instruments via Portuguese colonialism or other important points of musical contact, for example research on the arrival of Iberian string instruments in Angola through the presence of Portuguese and Brazilians between the sixteenth and the nineteenth century or the contribution of Angolan dances to Brazilian dances (Kubik 1997).

Special importance is given to the concept of lusofonia and the city of Lisbon as point of encounter for migrant musicians from the Portuguese-speaking world – respectively Lisbon as an open, cosmopolitan and multicultural city, attempting to include diversity as a source of cultural richness. According to Timothy Sieber, discourses of Lisbon as a sophisticated broker of transnational cultural flows go back to the 1990s. He writes that by then,

[a]lmost all discourses of national culture, history, and identity asserted Portuguese people’s historic facility in promoting dialogue and communication among the world’s cultures and nations and emphasized a history of mediation and brokerage, cross-cultural exchange and fusion, hybrid forms, and multiculturalism. (2002, 163)

Based on my discussions with the Brazilian ethnomusicologist Glaura Lucas, the Angolan dance researcher Ana Clara Guerra Marquês, and the information that the chances of Lusofonia, a (R)Evolução being screened on Brazilian television are «near to zero» (accessed 20 August 2013). I claim that a lusophone identity is not as important to other lusophone countries and capitals as it is today to Lisbon. Maria Manuel Baptista (2000) stresses that different lusophone countries indeed imagine different things under the «imprecise and ‹post-colonial›» term lusofonia. According to her, they experience this reality differently. The term lusofonia actually expresses asymmetrical power relations between Portugal and its former colonies. By representing Portugal as a «music market mix of different cultures», the documentary Lusofonia, a (R)Evolução moves Portugal, respectively Lisbon, to the centre of the lusophone world. Timothy Sieber questions if visions of lusofonia today differ from old imperialist ideologies and definitions of Portuguese national identity. At cultural events taking place at Expo ‘98 (Lisbon) he observed that European elements from Portugal were defined as providing the universal linkages among lusophone musical variants. However, what these Portuguese-supplied universals were, was not defined. Traditional Portuguese music was presented as «homogeneous, fairly static, fundamentally European and white» (2002, 167), and was separated from lusophone music. Sieber draws parallels to older lusotropicalist ideas where the inhabitants in the colonies were associated with miscegenation and hybridity, while Portuguese at home were perceived as homogeneous (ibid., 180). According to Vanspauwen, «the visibility of the musical influences from the Portuguese ex-colonies in Portugal is [also] largely denied [in música lusófona]» (2010, 71). Influences from Africa and Brazil are rather acknowledged in fado, a musical genre appropriated for Portuguese national identity, but not being Luso world music per se apart from when mixed with other musical genres.

Cultural products that promote societal values such as tolerance towards diversity, cultural openness and multiculturalism are today becoming national equities and foster competition within the market of global culture (La Barre 2010, 148). Jorge de La Barre uses the term «re-cosmopolitanism» for this process, pointing out that the process involves a post-national imagination but is still nationally defined and carries specific feelings of locality (or nationhood) (ibid., 150).

A transnational lusophone identity might strengthen Portugal’s position within the European Union and, so is said in the documentary, might help the country to «become bigger».18 Not only is Portuguese identity currently threatened by its participation in the European Union, but also lusophone identity by the strong influence of francophony and anglophony in Africa.19 As Sieber notes, «Portugal’s efforts must be understood as nothing less than a small-scale defensive holding action, designed to blunt overwhelming foreign domination, not only in relation to the former colonies, but also and perhaps primarily in relation to its own position within Europe» (2002, 183).

Although the purported lusophone commonality in música lusófona is the Portuguese language, musicians from the lusophone sphere sing in their local dialects and languages, too. The music industry’s division between music «in Portuguese» and «by lusophone artists» actually reflects the perception of lusofonia as a cultural system with various languages and cultures (Vanspauwen 2010, 31). A «lusophone identity» in the music is in the documentary identified as emotional states such as saudade and revolutionary feelings shared by citizens of different lusophone countries.

As a subjective narrative with journalistic treatment, Lusofonia, a (R)Evolução embodies the idea of a musical lusofonia ideologically. It shows how music served to integrate different cultures in the context of colonisation as well as in the migration context in Lisbon today, how it served as a tool for social intervention and for the globalisation of Portugal. The documentary ends up creating the reality that it promotes, namely «the blending between original musical elements from Portugal, Brazil and the Portuguese-speaking African countries […] and their inclusion in contemporary urban music genres» (press kit 2006, 4). Since parts of the documentary were uploaded to Youtube on 26 May 2012 (see here, accessed 13 August 2013), the documentary easily reaches its intended audience today. The documentary’s approach is rather mercantile in linking Portugal’s colonial past to the insufficient marketing of migrant musicians from Portuguese-speaking countries. However, the musicians shown in the documentary are already established in the context of the music industry, while migrant musicians at a grassroots level, i.e. those playing in bars, restaurants and associations, are not represented. Focussing on rather well known musicians «may well serve the goal of the documentary, reaching wider audiences» (Vanspauwen 2010, 46). Bart Vanspauwen further observes that the idea of lusofonia is «administered» by specific cultural entrepreneurs and that migrant musicians from Portuguese-speaking countries have their own agendas. In his master thesis, he explored how the concept of lusofonia affected the creative work of these migrant musicians and their opportunities to perform. He found that they did not identify themselves as «lusophone musicians», nor did the term lusofonia play a big role for them. They, however, saw some relevance of the lusofonia concept in the future, namely in the possible support by supranational institutions such as CPLP and national governments to promote and disseminate their music (Vanspauwen 2010, 60–66 and 70–72). While incentives for supporting Luso world music might have been lacking so far in the domain of the Portuguese recording industry, the idea of lusofonia has since 1998 musically been celebrated in festivals in Lisbon and abroad: in Galicia (Spain), Macau and other Portuguese-speaking countries, especially in Brazil.20 Furthermore, institutions supporting lusophone culture and language, so called «Casas da Lusofonia» («Houses of Lusophony») are becoming popular. In 2011, a Casa da Lusofonia was inaugurated in the Brazilian city of Fortaleza and in 2013, the first Casa da Lusofonia in Africa shall be opened in Cape Verde. The increasing popularity of the lusofonia concept and its realization in the cultural sphere, gives reason to expect that musicians from lusophone countries will continue to negotiate their identities based on this concept, be it through their own biographies, or, as the documentary Lusofonia, a (R)Evolução shows, based on Portugal’s colonial history and the impact of globalisation.21

Sounds

- 1. There is also a version of Lusophony, the (R)evolution with English subtitles.

- 2. DocLisboa is a film festival with the objective to screen films «that help to understand the world we live in and to find possible forces to change» (translated by myself from the website doclisboa.org, accessed 13 August 2013). DocLisboa has meanwhile also been extended to Cape Verde and Macau.

- 3. The present text results from a seminar that I taught at the Rostock University of Music and Theatre in 2012. I would like to thank Bart Vanspauwen and the editorial team of Norient for their comments and Kathleen Wiens for English language revisions.

- 4. Fnac.pt, accessed 13 August 2013.

- 5. RTP.pt, accessed 13 August 2013.

- 6. RBMA is sponsored by the Red Bull company based in Austria and is a non-commercial initiative including journalists, label heads, and musicians. It has been travelling the world since its foundation in 1998. Every year, sixty selected participants (musicians, producers and DJs) congregate in a chosen city for recording sessions, lectures, collaborations, and performances in clubs and music halls. RBMA also has its own record label, online radio and festival stages around the world. It aims at fostering creative exchange among people working with music from different countries, and getting «a rare glimpse into local musical hybrids» (RBMA website, quoted in Vanspauwen 2010, 38). It also teaches young talents the secrets of production and of music industry and transmits the know-how that enables them to make their mark in the future of music (press kit 2006, 4). For further information on the Red Bull Music Academy see Redbullmusicacademy.com (accessed 13 August 2013) and Sisario 2013.

- 7. The CPLP was founded in 1996 and is a Lisbon-based institution defending the political and cultural interests of all lusophone countries. It is financed by eight member states: Portugal, Brazil, Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, São Tomé and Príncipe and East-Timor.

- 8. Interviewees include the following musicians, musical groups and DJ’s: Carlos do Carmo, Sara Tavares, Tito Paris, Celina Pereira, Raúl Indipwo/Duo Ouro Negro, Kika Santos/Loopless, Kalaf, Cool Hipnoise/Spaceboys, Sam the Kid, Chullage, Tekilla, Melo D, Pac Man/Da Weasel, Conjunto Ngonguenha, Messias, Karlon/Nigga Poison, SP & Wilson (Beatbox), N’dú, João Barbosa, Tó Ricciardi, and Johnny-Cool Train Crew; the following publishers: José da Silva/Lusáfrica, David Ferreira/EMI, Pedro Tenreiro/A&R Norte Sul, Tozé Brito/Universal, Hernâni Miguel/‘Rápública’; and the following journalists and music critics: Nuno Sardinha/RDP África, Gilles Peterson/BBC Radio 1, Vitor Belanciano, Duda Guennes, Luis Maio, Rui Pereira.

- 9. For information on the labels of the soundtracks and clips see Vanspauwen 2010, 41.

- 10. The documentary draws on the following publications : Eduardo Freire de Oliveira, Elementos para a História do Município de Lisboa (1903); Jacques Raimundo, O Elemento Afro-Negro na Língua Portuguesa (1933); José Ramos Tinhorão, Os Negros em Portugal (1988); Dejanirah Couto, História de Lisboa (2000); José Machado Pais, Joaquim Pais de Brito and Mário Vieira de Carvalho, Sonoridades Luso-Afro-Brasileiras (2004).

- 11. The prefix «Luso-» derives from «Lusitano», the inhabitant of «Lusitânia», i.e. of the Western part of the Iberian Peninsula as designated during the Middle Ages. «-fonia» denotes a population that speaks a specific language.

- 12. The Portuguese expanded their territory to: North Africa (Ceuta, 1415), the islands of Madeira (1419), the Azores (1427), Cape Verde (1456), São Tomé and Príncipe (1471), East Africa (Mozambique, 1498), India (Goa, 1510), Malacca (1511), Sri Lanka (1539), Macau (1550s), Timor (1586) and West Africa (Angola, 1575); in 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral reached Brazil (dates taken from Newitt 2005). The last Portuguese colonies in Africa became independent in 1975.

- 13. In the documentary Tito Paris, the owner of Casa da Morna in Lisbon, calls for institutional action stating that «Portugal at this stage has, undoubtedly, a lot of potential. But the cultural entities, radio and TV stations, the ministry of cultural affairs, all must act now» (transcribed from the English subtitles of the documentary; Soares da Silva, Xavier, and Matos 2006); and José da Silva, editor of the record label Lusáfrica, based in Paris, suggests in the documentary that the lusophone world needs a budgetary system of incentives to expand its culture and to export it abroad (ibid.).

- 14. Saudade is the centerpiece of Portuguese «ethnic psychology». According to Kimberly da Costa Holton it is the Portuguese «sociophysic glue, the nationalist rhetoric which unifies centuries of melancholic travellers into a diachronic narrative of musical expression which ‹naturally› begins with the first heroic sea bound impulse off the shores of fifteenth-century Portugal. Saudade is also, according to many fadistas [fado musicians], the same emotional ingredient which enables fado vocality» (2006:4).

- 15. Kimbundu is a Bantu language widely spoken in Angola, especially in Luanda.

- 16. The classification of music into «rock», «pop», and «electro» in this text follows the use in Lusofonia, a (r)evolução (Soares da Silva, Xavier, and Matos 2006).

- 17. David Byrne (*1952, Scotland, living in the US), frontman of the band Talking Heads, has himself founded a world music label under the name Luaka Bop and, among musicians from Cuba, Africa and Asia, als produced Brazilian musicians such as Tom Zé and the band Os Mutantes.

- 18. The use of «bigger» is reminiscent of «Overseas Provinces of ‹Greater Portugal›», a term used for the Portuguese colonies during the era of the Estado Novo.

- 19. Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, and São Tomé and Príncipe belong today to the francophonie (f. 1970), and Mozambique to the British Commonwealth of Nations (f. 1976).

- 20. For example, the «Lusofonia Festival» in Macau since 1998, the International Festival of Lusofonia «Cantos na Maré» in Galicia since 2003, the festival «Lisboa Mistura» in Lisbon since 2006, the festival «Amor é Fogo» in Portugal in 2008, the «Io Encontro na Lusofonia» in Portugal in 2008 and the «Festival dos Oceanos» in Portugal since 2008 (Vanspauwen 2010:22,23,48).

- 21. I suspect that the concept of lusofonia has also influenced the Lusotronics Festival in Berlin in May 2013 (see «Lusophone Difference» in Frederick Moehn’s essay on this festival (2013) on Norient.com).

List of References

Filmography

Soares da Silva, Artur, João Xavier, and Mariana Moore Matos. 2006. Lusofonia, a (R)Evolução. Red Bull Music Academy. Documentary. YouTube, uploaded 26 May 2012, accessed 13 August 2013.

Trailer Lusophony the (R)evolution. YouTube, uploaded 16 November 2006, accessed 22 March 2013.

Sounds

Afonso, José. 1971. Cantigas do Maio. Discos Orfeu. LP.

Afonso, José. 1983. Milho Verde. YouTube, uploaded 23 February 2012, accessed 22 March 2013.

Bonga. 1974. Angola 74. Morabeza. LP. Cover at Website, accessed 19 August 2013.

Bonga (Angola), Marisa Monte and Carlinhos Brown (both Brazil). Mulemba Xangóla. Onda Sonora: Red Hot + Lisbon. Movieplay Portuguesa S.A. CD.

Dranoff, Béco and Andrés Levin. 1998. Onda Sonora: Red Hot + Lisbon. Movieplay Portuguesa S.A. CD.

Ferreira, Eunice. Fado de Cada Um. Soundcloud, uploaded 11 February 2013, accessed 22 March 2013.

Lulu & Lulucha, Morna. Un’Crebo Man Ca Ta Flabo. Written by Jorge Barbosa. Soundcloud, uploaded 12 November 2011, accessed 22 March 2013.

Pop dell’Arte. 1993. Ready Made. Different Star. CD.

Rapública. 1994. Columbia. CD.

Sam the Kid. Viva. Soundcloud, uploaded 19 May 2012, accessed 22 March 2013.

Tavares, Sara. Bom Feeling, YouTube, uploaded 13 October 2007, accessed 25 October 2013.

Tropicália ou Panis et Circencis. 1968. Philips. LP.

Biography

Published on March 06, 2015

Last updated on June 27, 2023

Topics

From Beyoncés colonial stagings in mainstream pop to the ethical problems of Western people «documenting» non-Western cultures.

From westernized hip hop in Bhutan to the instrumentalization of «lusofonia» by Portuguese cultural politics.

Does the global appropriation of kuduro exploit or reshape the identity of Angolans? How are «local» music genres like guayla sustained outside of Eritrea?

Snap