Mammane Sanni Abdoulaye played the possibly first synth organ in Niger and recorded his only album in 1978. Even his music until today is tootling as carpet of sound in the Niger TV, bigger part of the cassettes has disappeared. Christopher Kirkley from Sahelsounds not only found one of the rare copies in an archive in Niamey, he also found Mammane himself.

Lost in a music archive in the capital of Niger was the first I heard of the legendary Mammane Sanni Abdoulaye. The space was overflowing with dusty CDs, cassettes, and Nagra reels, and hunkering down from the insufferable heat outside, I prepared to spend a long week in research. Mammane’s cassette was the first I pulled from the shelf, and I almost passed over in lieu of something more obscure. But I was captured by the photograph — a black and white picture of a young man with a goatee and a knit cap, posing in front of faux backdrop, hands on what appeared to be an organ. The music proved equally intriguing. The instrumental compositions were simple but dreamy, repetitive but hypnotic. It was esoteric and bizarre, unlike anything I had ever head – the imaginary audio track to an arcade game of desert caravans trek through an pastoral landscape of 8-bit acacias and pixelized sand.

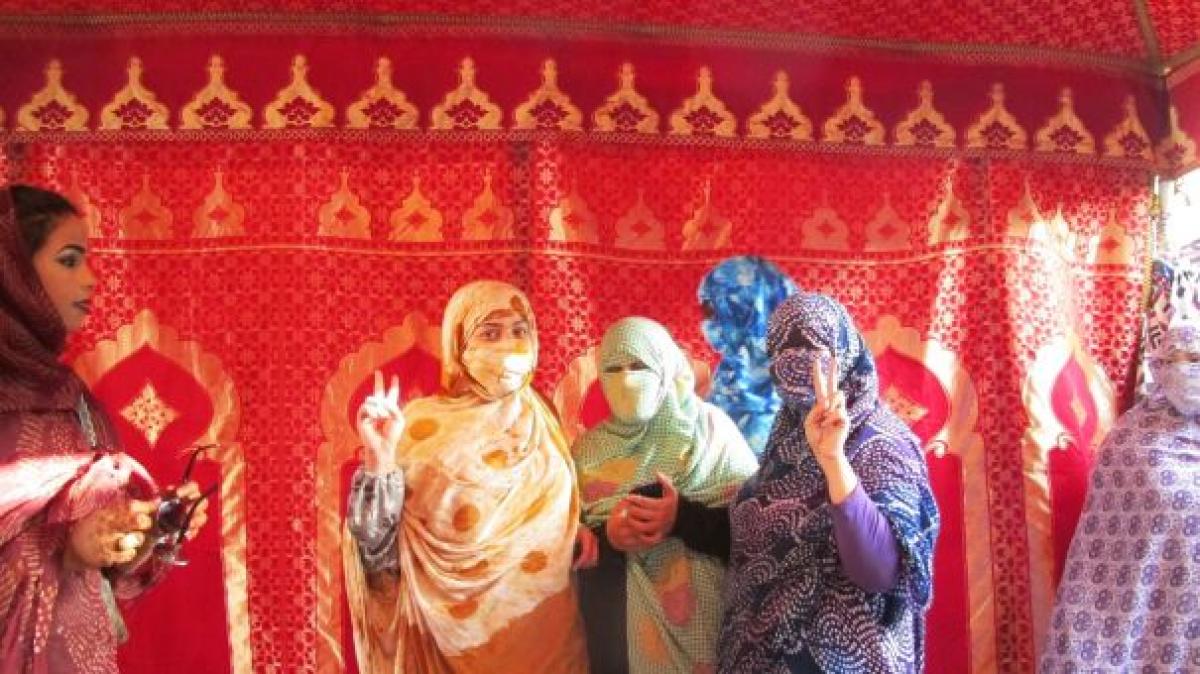

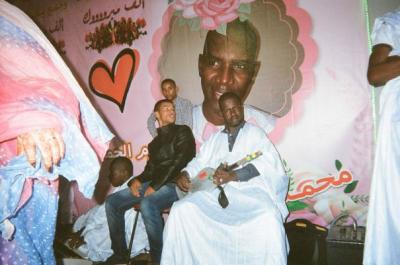

Finding Mammane was surprisingly easy. Immediately after asking about him to the archive director, I had him on the phone. The next day, Mammane arrived. Much older than in the photo, with greying hair and in a pressed shirt and slacks, he had a laugh when I showed him the cassette, and he said it was best if we spent the day talking – he was retired, and didn’t have much to do anyways. Moments later were running through the streets to catch a bus, followed by a taxi, that soon carried us outside of Niamey into the surrounding Sahel of scrubs and brown plains, where Mammane lives today. Inside the tiny house, interrupted intermittently by the persistent crow of a rooster, Mammane told me his story as we listened to his cassettes and paged through books of old photographs.

Mammane is well known throughout Niger, but his synth music was never hugely popular. He came from a privileged place in Niger society – his maternal grandfather was a chief in Ghana, his paternal grandfather a Colonel in the first World War, and Mammane’s father was a librarian for the American Cultural Center. As a young man, Mammane became a functionary for UNESCO, during which he traveled to Japan and Europe. During one of the UNESCO meetings, a delegate from Rwanda had brought along his Italian «Orlo» organ. Mammane was captivated by the sound and convinced him to sell it. «It was possibly the first Organ in Niger», he explained. He began to compose songs on the organ. Many of these songs were interpretations of Niger folkloric classics. «I wanted to make the Wodaabe songs on the keyboard, make the Tuareg tendé with the rhythm» he said. Some were his own compositions. Salamatu, one his most popular songs, was created for his girlfriend. He stopped as he came across her photo, how he once lay with his head in her lap, and tears came to his eyes. When she asked him why he was crying, he answered «Because I’ve never been so happy as I am in this moment.» He sits quietly, before I asked what happened to Salamatu, and he smiles before shaking his head and turning the page.

His first and only album was recorded in 1978. Mammane stepped into the studio of the National Radio with his organ, where it was transposed and overdubbed in two takes. In coordination with the Minister of Culture, the album was released in a limited series of cassettes showcasing modern Niger music. The cassette project unfortunately did not progress as planned, and merely a handful were released. Perhaps 100 were made – Mammane is unsure – fabricated in Nigeria. The copy that he owns and the one at the archive are the only ones he knows are left. Nevertheless, for over 30 years, Mammane continued to play. For a short while he even had a television show called «Mammane Sani et son Orgue Électronique» on Niger’s television. He digs out a short clip, a black and white video transfer playing in front of the same backdrop that graces the cover of the cassette. Mammane is hardly esoteric or forgotten in Niger. His music today is known by everyone – it forms much of the repertoire of televised intermissions, radio segue-ways, and background music. And Mammane has continued to update his organs and pianos when they fall apart, benefiting from generous contributions from high society, gifts of presidents and ministers.

I left Mammane’s house in the evening, ducking out of his house to catch transport back into town before the night came. And it was nearly a year later when we started to talk about releasing it on record. Mammane was nonchalant about it, only insisting that the proceeds could be used to upgrade his computer and get a new copy of audio software. But one of his musician friends I recently spoke to in New York was more adamant in his idea of the vinyl release. «He’s been waiting over 30 years», he said. «It’s about time.»