Lisu is a small minority group with a population of about 635,000 in China. Ethnography and Review of Yan Chun Su’s Documentary Treasure of the Lisu.

Lisu is a small minority group with a population of about 635,000 in China. They reside mainly in the Nujiang district of Yunnan Province. Outside of China, about 400,000 Lisu live in Burma, Thailand, northern India and the Philippines.

The Lisu’s origin can be traced back to the ancient Qiang tribe in the northwestern Tibetan plateau. Before the 8th Century, ancestors of the Lisu people lived in the upper Yangtze River canyon. After the 16th Century, the Lisu people had three mass migrations that brought them to the Upper Mekong and Nu(Saleween) River canyons.

Agriculture is the main activity of the Lisus, supplemented by hunting and gathering. The Lisus who live along the remote mountain areas by the Nu River canyon were kept mostly out of modern influences until the 1990s. Traditionally, the Lisus worshiped the spirits of nature and their tribal totems that became their family name. These nature worship include animals like tiger, bear, monkey, snake, goat, chicken, bird, fish, mouse, plants like bamboo, hemp, pear, etc, and also natural phenomena like fire, frost, etc. From the beginning the 20th century, some Lisu became Christians due to the influence from western missionaries.

The Lisus follow a calendar that separates the year into ten months based on the changes in their natural surroundings and their activities like the beginning of flower blossoming, the bird singing, gathering, harvesting, wine-making, hunting, house-building, etc. The language of the Lisu belongs to the Tibeto-Burma branch, with no written system historically. Western missionary invented an alphabetical written form that is used mainly for bible reading. At the beginning of the 20th Century, one tribe tried to create a pictogram written form.

Music is a vital element in the lives of the Lisus and music is performed in family gatherings, festivals, weddings, funerals, when they go hunting, herding, planting, harvesting, and even in resolving conflicts. According to the Lisu sayings, one can’t live without songs, just like one can’t live without salt.

There are mainly three types of Lisu music: folk singing, dance music and instrument music. Folk singing has three major forms. Mugwa is the type of songs that tell epic stories. They are sung during holidays, often along wine drinking. The lead singers of Mugwa are elderly men and the crowd follows in a chorus. The content of Mugwa is mainly around tribal histories, marriage and burial customs, work traditions, etc. Traditionally, when singing any Mugwa, a story of how monkey created the world was always added as a prelude. Mugwas from different regions have different name because of their content. In one of the tribes, when there is a conflict in the village, both parties involved would sing Beimo Mugwa back and forth in front of the judge who sings his opinion to the crowd. It is the only singing form known to remain in the world used for such purpose.

Baishi, or Baishibai, or Mountain Songs is another form of folk singing. The literal translation is «free to say, free to sing». Singers of Baishibai often form a line and dance to the rhythm while putting their arms on the shoulders of each other. It is sung around holidays, family gatherings, or just when doing everyday chores. Baishibai often happen out-of-door and improvisationally. There is a lead singer and the crowd is split into two or three parts harmony. Throat vibrato is used frequently and is quite characteristic in Baishibai.

Youyi or Love Songs is typically sung as dialogues between a man and a woman or a group of men and women forming a two parts harmony when they are out working in the field. Common themes include courtship, love, working, daily happenings, etc.

Dance music is a big part of Lisu music. Around traditional holidays or special events, people gather around the fireplace in the house or out in the open field, form a circle, sing and dance in various forms. Among them, Qian-er is a form of group dance popular around holidays in the Fugong area. The style is rather gentle, and accompanied by flutes, Chiben, and bamboo mouth harp, etc.

Ah-Chi Mugwa, meaning Goat’s Dance is popular among Lisus living in the high mountains. Lisu ancestors mimicked the sound and movement of goats, added that into the chanting during sacrifice ceremonies and created this dance form. No musical instruments are used. Dance beat is set solely by the vocal of the dancers. Each song begins with a lyric-less chanting that sounds like the callings of mountain goats. Various patterns are formed when people start dancing. When a circle is formed, it moves clock-wise most of the times. Dancers of Ah-Chi Mugwa used to braid their hair with wheat grass, men wear knife and women wear skirts. Even though such costume can only be seen in one Lisu village nowadays, the nature-mimicking characteristic is still very much present in Ah-Chi Mugwa.

Wa Ki Ki is a form of festive group dance that makes up of a total of twelve step moves in increasing complexity. Each step dance has its own name. Dancers typically form a big circle by holding hands together. Most of the body movements are on the hips and the legs. Flute, Chiben, bamboo mouth harp, etc. accompanied the dance with or without singings.

Music instruments used by the Lisu people include wind instruments like the Five-Pipe Free Reed Sheng, Bamboo Flute, Four-Hole Vertical Flute, Bamboo Mouth Harp or Kouxian; stringed instruments like the three or four-string plucked Chiben and a two-string bowed Jie Zi. For the four-string Chiben, the strings are tuned to the following notes: (c1 be1 g1 c2), (#c1 e1 #f1 #g1), (a d1 e1 a1), ((a e1 a1 e2), (c1 d1 e1 a1). Music performed by these instruments can be either a solo or an ensemble.

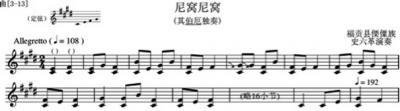

Below is a solo Chiben performance called Niwo Niwo (name of a bird):

Lisu music uses a pentatonic scale that normally does not include semitones. A, D Major are the main tones, followed by G, C major. Some use only three or two notes. When singing, followed by the lead singer, a chorus often forms by the crowd that consists of multiple parts that changes between singing in unison and two or three parts harmony. Harmonic intervals are mostly a perfect forth or fifth, making it easy to change from melodic to harmonic intervals. Lisu music is often played in even meters, seldom odd meters, typical rhythm is longs followed by shorts. Throat vibrato is often used in singing folk songs, reflecting the feeling of hardships people feel in their lives. Lyric in traditional Lisu songs is mostly made up of four or six sentences in one section, or three, seven, or nine sentences in one section. Typically, each sentence consists of seven characters. One sentence is often followed by another sentence that forms its antithesis which emphasis, adds, and deepens the meaning of the first one, and at the same time, makes the whole pattern more lyrical.

In 2009, Yan Chun Su came to Nu River Canyon in Yunnan province, China from the U.S. and stayed closely with Ah-Cheng Heng, a Lisu musician and tradition bearer and his family, observing their everyday life and researched the music traditions of the area. The resulting 30-minutes documentary provides a refreshing portrait of the simple yet rapidly changing life of an ethnic minority living at the intersection between a traditional and a modern world.

Ah-Cheng and his family live harmoniously in a remote mountain canyon. They work when the sun rises; rest when the sun sets, eat by the fire; play Chiben when there is time. When Christianity came to their village, Ah-Cheng and his family, as well as almost everyone in his village became Christians. They pray before every meal, sing hymns in the church, and follow defined doctrines by abandoning Lisu traditional music and songs in the church environments. But, with a strong sense of ethnic identity and the desire to carry on the Lisu traditional music he has mastered, Ah-Cheng still firmly maintains the craft of making and performing Chiben, one of the three treasures for the Lisu people (the other two are crossbow and knife, which Ah-Cheng is also skilled at making). He wants to pass his crafts on to the younger generation in the village and his offspring. But contrary to his wishes, his enthusiasm was met with the cold reality that younger generation is more interested in novel western music and instrument like the guitar while the ethnic instrument Chiben is largely ignored. This situation not only dampens Ah-Cheng’s well wishes and enthusiasm, but also presents an urgent need to protect this unique ethnic cultural heritage, a cultural memory that should not been lost.

With the arrival of electricity, digital communication and other modern conveniences, lives of the Lisu people have improved and been changed tremendously. The zip-lines that used to be the “road” between two sides of the canyons became bridges, the road down by the river connects to nearby cities, and many families own TV, cell phones, etc. These new changes and development offered people a lot of enticement and practical benefits. But, they also brought along huge impact to the cultural traditions in this used-to-be sheltered mountain area. Villagers changed their belief to the newly introduced religion, sang Christian music and followed western holidays. Their own customs and religion were gradually forgotten. Even though absorbing and integrating the new changes are good ways for development, blindly accepting and adopting without critical thinking will certainly result in the disappearing of ones’ own traditional culture, being assimilated, and eventually completely loss one’s ethnic identity, the soul and root of what makes the Lisu people who they are. The power of these impacts is immeasurable.

Yan Chun Su’s documentary, Treasure of the Lisu, tells an intimate story of an ethnic minority living in modern day China. It’s a world rarely seen by western viewers yet it attracts the audience and makes them contemplate. I appreciate the film’s deep meaning and its truthfulness and unpretentious representation of a simple life in a remote mountain village. We are left with deep concern for the Lisu people, their culture and the urgency to preserve it. For us working in the ethnomusicology field, we are especially alerted and inspired to continue this urgent and difficult task of helping to protect and preserve this important traditional culture.