Singing for Asian Autocrats

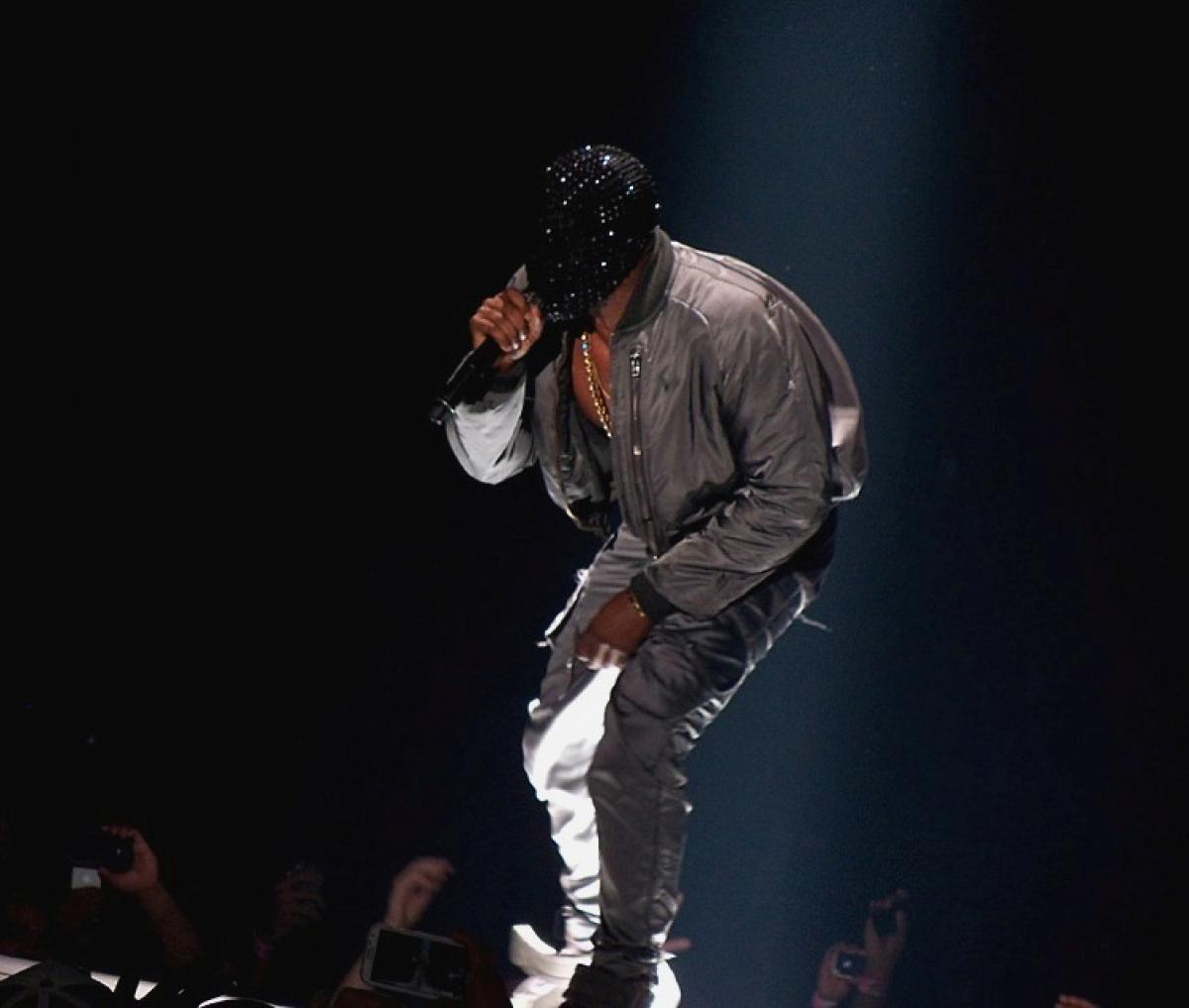

Jennifer Lopez, Kanye West and Rod Stewart did it. They pimped their income by playing court musicians in Central Asia. This places them at the heart of very dirty politics. Do they care? Do we care? From the Norient book Seismographic Sounds (see and order here).

Jennifer Lopez did it in Turkmenistan, Kanye West in Kazakhstan, Rod Stewart, Julio Iglesias, Ennio Morricone and Lara Fabian in Uzbekistan. Sting, too, did it in Uzbekistan – and then almost again in Kazakhstan. Certainly, somebody did it in Kyrgyzstan and Tadjikistan.

To perform for authoritarian rulers or their family members in the post-Soviet world has become a lucrative business among the stars and superstars of international pop. Whenever journalists manage to uncover artists’ public or semi-private adventures of this kind in Central Asia or other postsocialist states, events follow an almost ritualised pattern: on the part of the western press, there are harsh accusations of inexcusable political ignorance to spiralling poverty, large-scale corruption, extensive exploitation, rampant nepotism and horrendous torture in the respective countries. On the part of the artists, these accusations are countered with remorseful avowals of exactly this inexcusable political ignorance – either in a self-chastening variant («Had only I known, I would not have performed!»), or by blaming others («Had only my management worked properly, I would not have performed!»). Very rarely do artists muster the breathtakingly paternalistic chutzpah of Sting and defend these performances as musical development aid for a culturally isolated, deprived and suffering people.

A Three Million Dollar Wedding Gig

Artists’ attempts at concocting convincing subterfuges are mostly bizarre in nature. No less bizarre, however, is the tremendous media outrage that their musical excursions into the post-Soviet East regularly evoke in the first place. It seems quite quixotic to expect artists in this league (or artists in general, for that matter) to act as moral role models when dealing with the excesses of Central Asian sultanism and its likes. How come we seriously expect Kanye West to decline an (alleged) three million US dollar offer for playing the wedding of the Kazakh president’s grandson due to political scruples? This, I would claim, has less to do with insights into Kanye West’s political convictions and conscience than with the tenacity with which we like to cling to the romantic idea of artists as being oppositional – as if this profession were primordially or intrinsically loaded with the task of exposing and fighting the bad in the world. This, however, is more of a moralistic fantasy than an expectation informed by reality. After all, in the global history of music, considerably more musicians have aligned or arranged themselves with political power (even of the most dubious and violent kind) than denounced or resisted it—not only, but very often for economic reasons.

Why, then, do we so insistently expect political opposition from musicians, or at least «political awareness»? Because it puts us in the pleasant company of heroes and heroines, many probably decidedly more heroic than ourselves? (Honestly, who of us has ever thought or done much about the political situation in Central Asia?) Because it elevates us to the comfortable position of moral superiority from which to criticize those musicians who do not meet our expectations? Whatever our reasons, maintaining political opposition as a template for musicianship will tell us little about those artists that are unwilling or unable to become heroes and heroines – and that is probably about 95% of all musicians worldwide. It will also help us little in comprehending the relation between musicians, power and money in Central Asian thought. And all of this, unfortunately, leaves us with very little to know and say about the topic at all.

The text was published first as a very short quote in the second Norient book Seismographic Sounds.

Biography

Links

Shop

Published on January 26, 2018

Last updated on April 30, 2024