Sampling Stories Vol. 2: Ibaaku

Although it has been labeled as an afro-futuristic project and also comes along as such through an eclectic and stylistically hyper diverse sound collage, photographs that evoke moonscapes, alien-like fashion and hairstyles, and music videos with an out-and-out futuristic aesthetic, the 2016 album Alien Cartoon by Senegalese producer Ibaaku (Akwaaba Music) is deeply rooted in current (and also past) places. Connections to Senegalese places such as Dakar or the Casamance can be heard throughout the album and become especially obvious when focusing on the samples used.

Ibaaku's music owes to Dakar’s buzzing and sprawling urbanism, home to his recording studio, as much as it does to Casamance’s green stretches and to Sardinia’s rugged landscapes, where he likes to retreat, getting lost to better find himself.

This is how a label-statement reads and how I got curious on how one actually can hear these places through the music. Via email and Skype I discussed these kinds of questions with Ibaaku.

[Hannes Liechti]: Your record studio is situated in the Senegalese capital Dakar. How can we hear the city in these tracks?

[Ibaaku]: Tracks such as «Discuting Food», «Ilwaa», «Yang Fogoye», «Djula Dance», and «Processhun», are clearly inspired in some ways by the noisiness of the place where I live in Dakar. There are loads of factories and auto mechanics around and there is a weekly market, which has its own inspiring soundscape. Everyday you can be sure to hear an army of sabar (a Senegalese percussion instrument) rehearsing or playing for a celebration. In «Muezzin» you can even hear my neighborhood in Dakar with a muezzin, who makes the call to prayer.

[HL]: How did putting this sample into the track come about?

[IB]: Muezzins are part of the soundscape in my country. In general, they use rather rudimentary equipment: megaphones, bad microphones, or very bad speakers. You can hear them blast from miles away. But I didn't have to enter a mosque, it came to me naturally because I live in front of a mosque. So I was deep in the creative process, experimenting, and it came by accident. The call slipped into the recording I was making at one point. I did not notice it at first. But when I heard it, I felt like I had to use it. I like accidents in music. It's my way of doing things. I love to let space for intuition.

[HL]: Does the muezzin sample carry a special meaning to you that goes beyond the circumstances of the production?

[IB]: At the end there is always a meaning to these kinds of accidents. The muezzin sample fits so well because it sparks the idea of a spiritual ritual, which is the intention behind some of my music.

[HL]: Can you tell me more about the way you sampled the muezzin? What were your strategies? Did you alter the sample, did you use any effects?

[IB]: I edited a part where he's calling the name of God. I didn't add a lot of effects. I kept it raw. A little reverb and a delay, and it was perfect.

[HL]: If we consider the label statement I quoted above, we can discover more places in Alien Cartoon. What about the Casamance for example? In contrast to the country in general, a very green, subtropical region in the South.

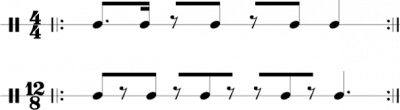

[IB]: When you listen to tracks like «Djula Dance» or «Processhun» the rhythm is clearly rooted in the Casamance. It is repetitive, raw, spiritual and transcendental. It is a rhythm played by the Jola (Diola) people [an ethnic group living in the Casamance; editor's note] on a percussion set called a Bougarabou. There's also another component to this rhythm that has influenced me – the clap part.

[HL]: The «rugged landscapes» of Sardinia» have also been mentioned. How can we hear this connection?

[IB]: Traveling is always an inspirational source for my art. I kind of absorb everything in Sardinia, the sea, the mountains, the people, the lights and colors, the silence, the food, everything! But to be honest, especially for this project, it wasn't a part of the mood. This is more about Africa.

[HL]: Can we hear more places in «Alien Cartoon»? If so, which ones?

[IB]: Yeah sure. I've sampled a lot of old Congolese celebration music mostly out of the 70’s, especially voices. All of them are taken from vinyl.

[HL]: In some reviews, these samples have been discussed as «Senegalese» samples, right?

[IB]: Yes, they are referring to the «Congolese» samples. Actually, I've only used one or two «Senegalese» samples on Alien Cartoon.

[HL]: What else can we hear?

[IB]: You can also hear some places that exist in my imagination, or places I knew when I was in other lives.

[HL]: Here we close the circle to the main subject of the album: Alien Cartoon as a futuristic manifesto.

[IB]: I blended all those sonic influences I told you about and put them into a futuristic perspective: an African city invaded by aliens. Dakar is a mutant city. So it was really interesting and challenging to imagine how music would be if extraterrestrials were among us.

The interview has been conducted via Skype, 27.6.2016. This article has been published in the context of the PhD research on sampling in experimental electronic music by Hannes Liechti. For more info click here.

Biography

Published on January 31, 2017

Last updated on October 26, 2020

Topics

Why do people in Karachi yell rather than talk and how does the sound of Dakar or Luanda affect music production?

Why does a Kenyan producer of the instrumental style EDM add vocals to his tracks? This topic is about HOW things are done, not WHAT.

Place remains important. Either for traditional minorities such as the Chinese Lisu or hyper-connected techno producers.

Sampling is political: about the use of chicken clucks or bomb sounds in current music.

Special

Snap