Hyped singer of the Arab world, co-founder of an early Lebanese indie band Soapkills and a role in a Jim Jarmusch movie. Yasmine Hamdan talks about her fascination for Asmahan Al-Atrash being the first female punk and Western misconceptions of the Arab worlds.

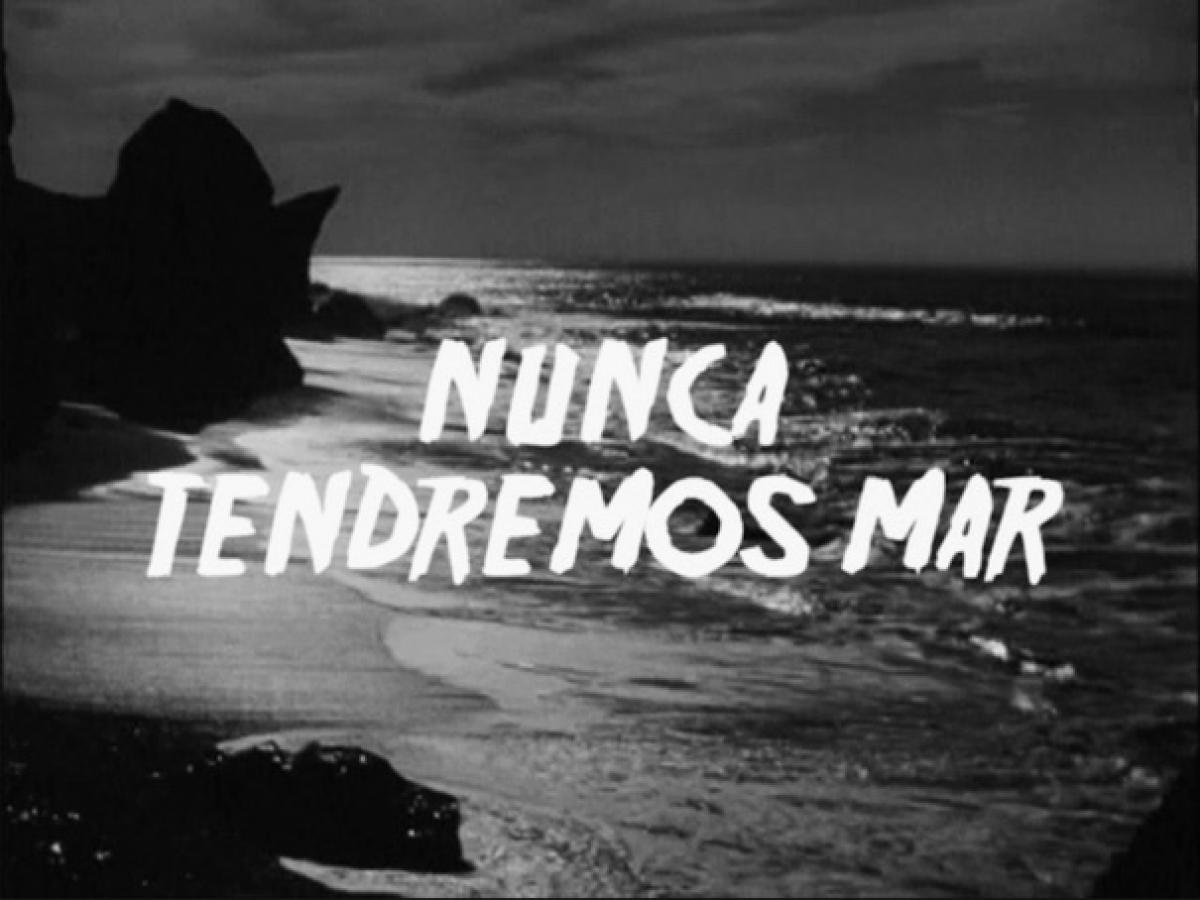

Born 1976 in Beirut, Yasmine Hamdan grew up in Lebanon, Kuwait, Greece and the Arab Emirates. In postwar Beirut she co-founded Soapkills, a duo project with producer Zeid Hamdan which is said to be the first independent band in the country. She moved to France where she collaborated with producer Mirwais as floor friendly electronic YAS, before going solo in 2012 with the highly praised album Ya Nass. Since then Yasmine Hamdan has gained further recognition with an appearance in Jim Jarmusch’s vampire romance Only Lovers left Alive and has performed almost non-stop for three years while working on her second album called Al Jamilat. The title track («The Beautiful Ones») is an adaptation of a poem by Mahmoud Darwhish. In other songs she is switching between classical Arabic and local vernacular, her voice hovering over a refined, brooding and instrospective soundscape with lots of space, long atmospheric intros and beautiful instrumentation. Al Jamilat is released on Crammed Discs, the video to the single «La Ba’den» was directed by her husband, filmmaker Elia Suleiman.

[Eric Mandel]: Since Ya Nass, it seems you have been touring relentlessly, I guess we can be lucky that you managed to get an album done.

[Yasmine Hamdan]: Actually it was kind of hard to find some solitude. As an artist you have to do a lot of representation, and this can be very draining. If you write an album you need solitude, a slower pace, something that is more contemplative. This time I wanted to be more central to everything, artistically I wanted to be more in the lead. A lot of the songs were born on a plane or in the train. I also tried different places like hotel rooms. It helps you a lot, because it allows you to take a bit of a distance and kind of feel the songs in different environments, like you start feeling the temperature of the songs in each place you are.

[EM]: In terms of temperature the album feels very warm, intimate and subtle. Like a sanctuary in a crazy world.

[YH]: I think music in general has always been a place to hide. A place that allows me to be more in touch with my spiritual self and where I am really being able to be in a different space, it's really about slowing down and spacing out. So when I'm working on songs I need to be dreaming, I need to feel something emotional and I need it to be very sensual. Imagine you need to have something that makes you feel better or ease your pain. All the artists I listen to have this spiritual dimension and this relation to time and space. I like silence in songs.

[EM]: Lyrically you held on the Arabic language. Wouldn’t it be easier for you to sing in French or English for the international market?

[YH]: Arabic is my emotional language, in which I feel I can really bring something new. A lot of people have done so many things in English, I cannot compete with them. I learned five languages. I always felt that they give you the freedom to think in different ways. There are many words in English that do not exist in Arabic, and the other way around. But language has always been something very universal. I started singing in English without understanding one word. I fell in love with a lot of artists that I do not understand, and do not care to understand what they are talking about a as long as there is an emotion that passes and talks to myself. If you let your mind think and you don't let your body and your senses let go, you cannot space out with the music and be in another, kind of chemical relationship [with it]. So I am really more with the chemical relationship.

Surfing Between the Dialects

[EM]: You sort of carved your way into the Arabic musical language. You had to find a way to adopt the singing traditions for your needs and purposes. Does this give you more room for experimentation?

[YH]: Of course. I know a lot of dialects, as I lived in many different Arabic countries. Each dialect has a different sense, musicality and way of grooving. I like to surf between these dialects – to sing a song in Egyptian, then in classical Arabic, and then in Lebanese, and then turn to Kuwaiti or Iraqi or Palestinian. All of them can sound differently, and that gives me a lot of possibilities with the melodies. Because they don't always work with the words. It's very difficult to find the right balance.

[EM]: So you can paint a more detailed picture with subtle means, which for Western ears makes not much of a difference. Do you sometimes have the feeling that you are talking to two audiences? One that can feel the music, and see you and be convinced by the overall appearance and one that can actually dig the poetry?

[YH]: My songs have not always been accessible for Arab speaking people all the time. Not everybody is comfortable with, or used to the Kuwaiti dialect. I do a lot of references in my texts to things that are very local, or that come from my childhood, my past, cultural things we all share. Many of us grew up with Egyptian cinema and music, on things that, at some point, nourished a whole generation of Arabs. So I like to have this past in the presence of my songs. It gives me somehow more freedom to sing in front of a public that gets the melodies, the presence and the music in a different, more abstract way. And I think, from these two places, people meet. There is no border between one audience and the other. Because somehow there is something they can share. It's the same thing in art. We share some love for the same thing, but for different reasons.

[EM]: Here’s an example: I read what sparked your work was a song by Asmahan Al-Atrash.

[YH]: It was many things, but on an abstract level, she opened the door for me. She was this incredible Syrian singer who died at the age of 33, very beautiful and with this incredible voice. In her songs there are a lot of different influences and sonorities from different worlds: The Arabic world, but then there is also a piano and very edgy and modern things in there. Also, she mixed opera and Arabic music in the most elegant way. She was a Syrian princess, got married and divorced three times with the same prince. Everybody thinks that she was a double agent, and there are very weird stories around her. But aside from her being very mysterious, I really felt the fragility and melancholy behind this powerful voice. I fell in love with her instantly – also because my grandaunt, who was like my grandmother, used to sing me her songs, and I hadn't heard them [from anybody else]. So this was the first time I heard this song with her voice. My heart (sighs) ... I was very happy.

[EM]: Asmahan was a very modern, a woman ahead of her time, in a way, compared by some with Marlene Dietrich.

[YH]: Completely. She was not very lucky to have been born in this environment, because she always had to somehow please a lot of people, I think. It's not easy being a princess and a singer I guess [laughs].

[EM]: What song was it, by the way?

[YH]:It’s called «Ya Habibi Ta’ala», written by her brother Farid Al-Atrash, and it is said that it is based on a Mexican song, which you can hear when you sing the melody.

[EM]: That figures, it has a sort of bolero or habanera feeling to it. But you never recorded it?

[YH]: I did actually, with Soapkills. This was the first song I recorded in Arabic. I had a 4-track and I produced a lot of crazy demos [laughs]. But we never really released it. You know with Soapkills nothing was really official, because it was so underground. We didn't really care, and the times were different. I don't even have pictures of Soapkills. I am happy that Zeid exists, because he is the one who kept a little bit [laughs]. I was more into that idea of doing things in the moment, you know. We did a lot of songs, but we did not record them all, and if we recorded we might have recorded at a party or a concert, but badly.

We Are Not All the Same Arabs

[EM]: Over the last three years you gave interviews to every media that matters in Europe. Did you have the feeling that people come to you and want you to explain the state of the Arab youth, especially in connection with the Arab spring?

[YH]: I have been asked about the Arab spring but not too much. There is a sense of wanting to understand something that is eventually not one place. We are not all the same Arabs, and actually it a false name. On the cultural level there are things we can sometimes share. But on many other levels we are very different. So yeah, I had people asking me questions, and sometimes wanting me to fill a format, a stunt title like «The Arab Voice» or whatever. It's fine, it's not a bad thing. What I think is really bad is to only talk about the bad guys who are somehow very foreign to us, too. Just as much as in Europe we are just discovering and really suffering from these movements that call themselves Islamists. For me they are mainly a result of the world we live in, and it's not our invention. So it's good that the media can somehow emphasize on different things. That at least creates pockets where people can dialogue and have conversations.

[EM]: Still you came back to the term in a different way in your lyrics, where you sort of re-name it, talking about «spring for Arabs». What’s the difference?

[YH]: Spring is spring, and I can relate to it somehow, but in a kind of twisted way. For me spring is hope, ending of winter, beginning of a new life. The sun comes back, and there is something really refreshing about it. But of course I am also referring in some twisted way to the Arab Spring but I say «spring for Arabs».

[EM]: What other misconceptions did you encounter when you talked to Western media?

[YH]: I didn’t really encounter a lot. I would say 90 % or more of all people I met were nice, curious, respectful and inspired. I wouldn't say I was insulted or felt ghettoized. Sometimes I got some [bad energies], sometimes even in the Arab world. For a while, when it came to mainstream media, they would say: You are controversial, you are subversive, and provocative, and that has sometimes put me in the defense. I have a strong character, I am free, and I am a woman. I guess it is more challenging for a woman to be herself bluntly, and show her weaknesses and her forces. I guess this is how it is, but now it has changed. I also had some not interesting interviewers who wanted to put me in a corner – rather in UK and France, than in Germany – that goes with a post colonialist perception. Some people cannot get rid of it. So they look at you and ask you question from this point of view. That got me a bit, well, not interested. But that's where it ended.

The Stupid Show Will Ever Be Stupid

[EM]: When you came to perform in Lebanon, did you feel in the reception, that the pride of your success outweighs the provocation?

[YH]: It's not about Lebanon, as it is the most progressive country. In many places in the Arab world, sometimes, I felt that I was bugging. I don't know how it is now, I performed in Lebanon and Egypt one and a half year ago, so it has been a while, and I think that things are changing. You have conservative societies like in every place, and you have really interesting individuals, who are trying to change things, and they have visions, and that is very refreshing. So it depends on where you perform, in which venue, in front of what public. If you decide to do the stupid show, the stupid show is going to be stupid. They will ask you stupid questions, and you are not going to be much challenged. Or if you decide to do this type of interview that might give you a little bit less exposure but a better quality of conversation … it really depends on the context.

[EM]: How did you experience Beirut the last time? When you started with Soapkills you formed it out of nothing. 15 years later ...

[YH]: …now you have a lot of bands, and people are going out, go see concerts, bands come from abroad. When we started this didn't exist. Even the underground idea didn't exist. It was very challenging, you didn't have venues, or musicians, you didn't have anything that would allow you as an artist to evolve. And it posed some problems for me, as I was really stubborn, and my parents were really worried. They thought I was a teenager doing her teenage crisis, you know, forever. They didn't understand that this was something I was ready to fight for. They didn't trust that I would find my way, because they didn't know what it was. You had the generation gap and the cultural gap, and then there was the reality on the ground. The country was half destroyed; people were not very open to this kind of propositions. And eventually, I am a girl and I should not do this, and should not perform in certain places etc. But I am really happy that we started at a time when things were not ready in the country. Everything about the place was emotional; it felt very melancholic, yet very hopeful. But I don't have the same relationship to Beirut any more. I do have my family, and some of my friends - but many of them left.

[EM]: This time you recorded in New York.

[YH]: I recorded in four countries actually: New York, Paris, London and Beirut. I finished it in London and I started it in New York. I had a lot of fun and I met a lot really amazing musicians. I was very lucky, because it could have been really a disaster, because a lot of people I worked with I didn't know. Many of them came to the studio hearing the songs for the first time and then just performing. I was lucky to have two really elegant and talented and brilliant producers. I really wanted to take the lead with this record, so I came with very advanced recordings, because I had composed and edited and recorded more than 80 % of the record. I wanted to be in this place where I could allow the songs to evolve and become different, but I also wanted the songs to arrive at a certain maturity, and to adopt the vision I had for them, so that they would become more flexible

«I'm a Result of a Remix»

[EM]: If I would DJ tonight, what song would you recommend?

[YH]: «Café» would be a nice song for a DJ set I guess. And the last song, Ta3ala, is a song like this. I really am into Kuwaiti grooves, and I asked a friend of mine who is a programmer to program this Kuwaiti groove. It was really fun for me, because Kuwait grooves, they have something, I wouldn't say R'n'B, but probably very blackish. And at the same time, the accent, the way it grooves, is completely lazy. You don't understand how, but there is the feeling of a camel walk, a camel walking through the dunes, that was really fun.

[EM]: Last up: This site is called Norient, my radio thing I call the FreakOuternational. But when it comes to talking about music and culture it's always hard to escape a bipolar thinking about the East and the West, the so called Orient and Occident. How do you relate to that?

[YH]: I don't see that. I am the result of a remix. I think borders are borders in the peoples' heads, and these are borders that people drew. I mean we are all human, we all want to be happy, we all have problems, we all have ups and downs, and in the end we are going to die. At the end of the day we have a lot in common. I like this place where borders don't matter. I have been fighting against them in my life. In my life borders brought only pain and loss of time and money, as unfortunately I was born with the wrong passport. Now I have a French one, and my life has changed, which is just absurd. It is very unfair, but that is the world we live in. Borders for me are the lids that people put onto each other. So I don’t see that gap, and that is a reflection of the fact that the world has become like that. People travel all the time, people are very mixed, you have 4th generation immigrants everywhere in the world. Unfortunately there is this tendency to stay attached to the racial, the religious, to identity. And the identitarian aspect is really in contradiction with the world we live in.