Heavy Metal Queens

In Botswana, heavy metal is a subversive form of self-expression, especially if the fans are female. The South African photographer Paul Shiakallis captured the metal «queens» in their homes. Norient spoke to him about his experiences with the Marok.

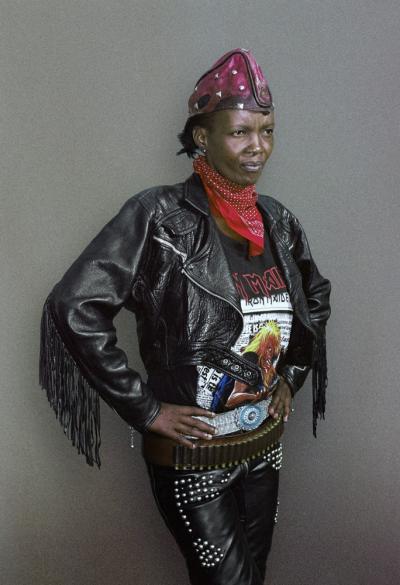

If we look back in history, popular music has always been an ambassador for ideas of freedom, self-expression and empowerment. In Botwana’s conservative and patriarchal society, the heavy metal scene, locally known as Marok («rocker» in Setswana), is a source of individual and collective empowerment. When the South African photographer Paul Shiakallis traveled to Botswana in 2011, he was especially fascinated by the female fans, who are referred as «Queens». A few years later he captured some of the leather-clad women in their private homes. Norient spoke to Shiakallis about the obstacles in his work and the contradictions of documenting a subculture within a (male dominated) subculture.

[Philipp Rhensius]: What was the idea behind your project?

[Paul Shiakallis]: I wanted to photograph the females of the Marok movement. The men had always been at the forefront of any media coverage. It was very fascinating for me to see black people wearing full leather outfits and listening to heavy metal music; and even more fascinating to see african females doing it.

[PR]: Considering Botswanas patriarchal society it seems that it wasn't easy to find these women. How did you approach your research?

[PS]: It was quite difficult indeed. The Marok is a very underground cult. They don't usually wear their full leather gear during the day, so you won't recognize them in a crowd unless you knew what you were looking for. I live in South Africa, so when I came back from Botswana my only connection to the Queens was through social media and text messages. My other connection to them was one of the first rockers I met. She was very willing to help me find Queens.

[PR]: The term queens could also be understood pejorative…

[PS]: The females tend to call themselves Queens. And by doing this, even more evidently than the men would call themselves Kings. In South Africa, if you had to call someone a Queen it would be an insult, implying that they are a diva or that a man is gay. But for them it is empowering. I think this is a step in the right direction.

[PR]: Did you have any obstacles in photographing them?

[PS]: There were numerous obstacles. The Queens tend to be quite shy, although they are powerful, confident people at the rock shows, they tend to be more reserved in normal society. Since I was a newcomer from another country, and particularly that I am a white male, they were quite wary of my intentions. Some of the Queens were still «coming-out» as rockers and they were afraid of where their images would go. Another factor was their husbands and boyfriends. Some of their men were so possessive and controlling that they would thwart the shoots; some did not want their women to be in the presence of another male; and some did not want their women to have the same recognition as they did as rockers. 90% of the portraits I shot almost never happened.

[PR]: To what extend did you feel the need to give these women a visual voice?

[PS]: I felt like I needed to give the Queens a voice as they are under-represented. It is much harder to become a rocker as a female than it is as a male. From my experience, Botswanas society expect their women to be subservient, to be lady-like and to set a good example for their children. The females receive so much more criticism from the general public. It requires a thick skin to maintain a rocker lifestyle.

[PR]: The Marok movement seems to be subversive on an unconscious level...

[PS]: The Marok in general are not rebellious against any systems. They do it more for self-expression, individualism and camaraderie. They tend to work as public servants, soldiers, police officers etc. And through this they are quite a disciplined bunch.

[PR]: But this is just the surface, isn't it? Being a female rock fan seems to be clashing radically with specific religious or social rules.

[PS]: The general public is quite religious, a lot of people attend church regularly and 90% of TV consists of church based channels. The Queens complain that the public labels them as satanists; it’s the most common insult they get. This is just the normal church-goers perception of the Marok, and it is a misconception, as many of the Queens have normal lives and attend church regularly. They understand belief systems better than the general public. The Marok is somewhat of a belief system; it's about how music can unite people and how it can be a catalyst for change.

[PR]: Did you have any experiences regarding the accusations of being satanists?

[PS]: One of the Queens told me that her church tried to dispel the demons from her body to make her stop listening to rock music and following the Marok. She agreed to let the Pastor try, just to prove to him that it was her choice and not that she was possessed.

[PR]: Would you consider yourself as being an artist or an ethnographer?

[PS]: For this project and for upcoming projects I would say my work takes more of a critical ethnography approach. I look to highlight those that are victimized, marginalized and are looking for a voice.

Biography

Published on March 16, 2016

Last updated on April 10, 2024

Topics

A form of attachement beyond categories like home or nation but to people, feelings, or sounds across the globe.

Why is a female Black Brazilian MC from a favela frightening the middle class? Is the reggaeton dance «perreo» misogynist or a symbol of female empowerment?

From priests claiming to be able to shapeshift into an animal to Irish folk musicians attempting to unify Protestants and Catholics.

From westernized hip hop in Bhutan to the instrumentalization of «lusofonia» by Portuguese cultural politics.

Snap