Making Persian Music More Accessible to Outsiders

How can a composer of contemporary music use the micro-intervals of traditional Persian music as raw compositional material? How can we convey these micro-intervals to performers regardless of their cultural background? These are questions asked by the artist–researcher Arshia Samsaminia in both his artistic and academic work. In this article, he summarizes some of his findings and draws on the history of microtonal Persian music and its notation, beginning in medieval times.

Compositions based on Persian dastgāh/maqām1 music with its specific intervals can be challenging for performers unfamiliar with Iranian music. Performing maqāms on instruments whether fretless or fretted is less of a challenge for musicians well-versed in performing traditional Iranian music, because of the abundance of these intervals in this country’s music, including lullabies, folk songs, popular music, and the audible media spheres. Thus, along with the experience of belonging to a certain world region, these factors can be a reason why a person’s ear becomes more accustomed to these intervals.

Composing for electronics, however, can open up a way for performers with a different musical upbringing to develop an understanding of Persian dastgāh/maqām music by introducing the specific intervals to the computer software being used. The results of my research in this field, which I will summarize in this article, became the core of my doctoral dissertation «Composing Based on the Iranian Maqāms and Tunings Using HEJI Notational System».

Medieval Roots: Safī al-Dīn al-Urmawī

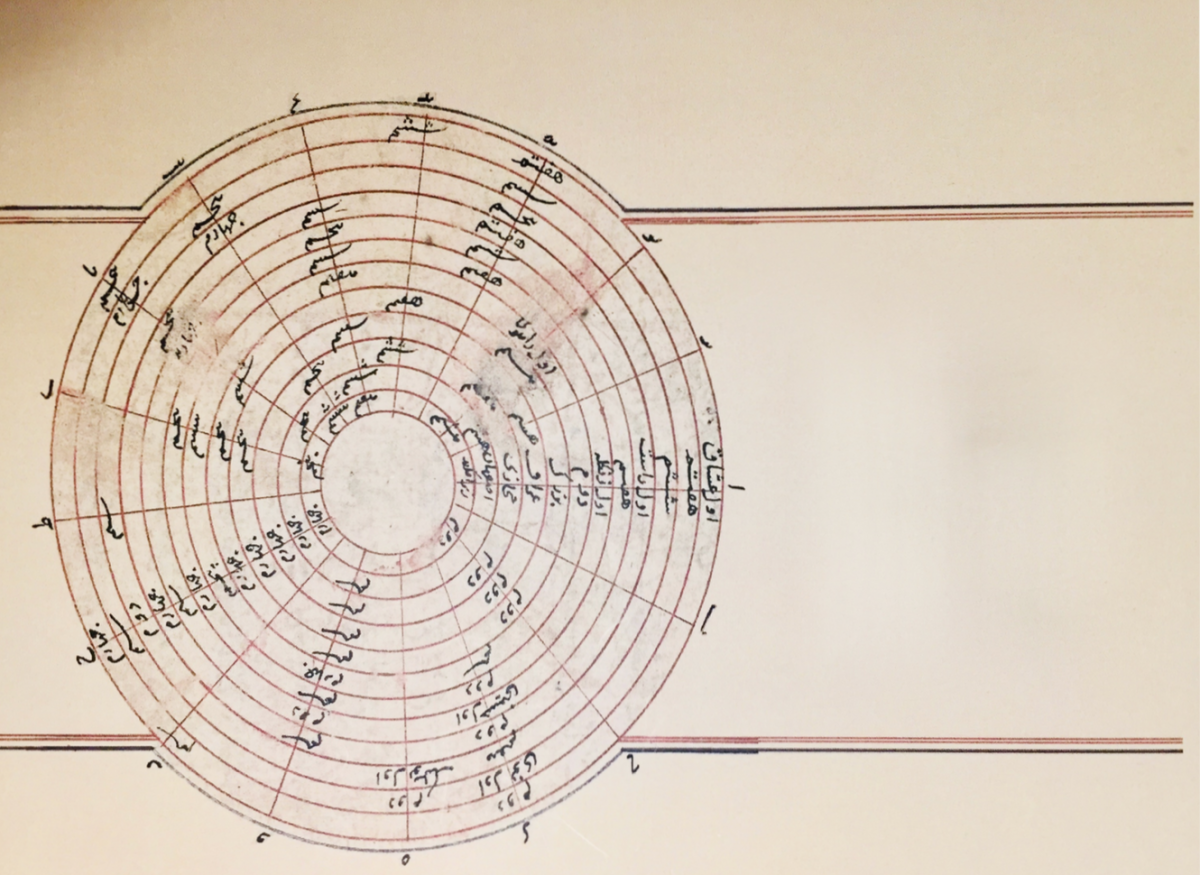

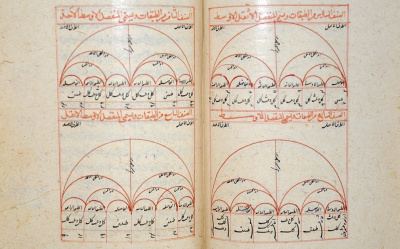

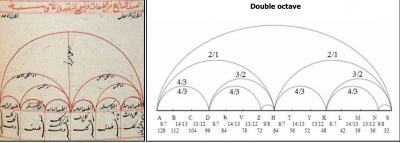

In traditional Persian music theory, as well as the music of other Islamic countries, the book of al-Adwār is the first extant work on scientific music theory, written by the musician and music theorist Safī al-Dīn 'Abd al-Mumin al-Urmawī in 1267. Al-Urmawī used the abjad notation, an alphanumeric code in which the 28 letters of the Arabic alphabet are assigned numerical values, to create music with and without lyrics. In this way, all musical intervals were also precisely defined. However, his theory was based on Pythagorean tuning, whereas as the maqām evolved into the dastgāh, Persian instruments began using some form of temperament.

The 24 Equally-Tempered Division of the Octave (EDO): Ali-Naqi Vaziri

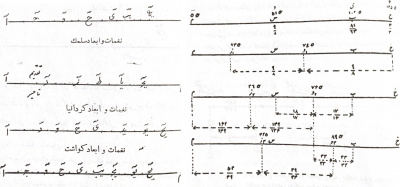

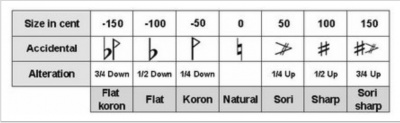

In the 20th century, 700 years after al-Urmawī’s theory al-Advār, the composer, educator, and musician Ali-Naqi Vaziri (1887–1979) introduced a 24 equally-tempered quarter-tone scale. Vaziri was one of the first Iranian musicians who traveled to Europe to study music. In France, he studied the principles of harmony and composition, as well as the piano and violin. In his book Musiqi-e naẓari, first published in 1934, he set forth the proposition that all the modes of traditional music could be conceived within an octave scale of 24 equidistant (tempered) quarter-tones. There are two main microtonal accidentals developed and practiced by Vaziri, influenced by Western music notation: Sori, which raises a tone by a quarter step up, and korun, which lowers a tone by a quarter step down.

However, I believe that Persian music intervals are not as simple as explained by these accidentals suggested by Vaziri. But how can a composer of contemporary music use micro-intervals of traditional Persian music as raw compositional material instead? How can we convey them to performers regardless of their cultural background? How can these intervals be introduced to computer software to allow performers to hear the right Persian scale?

Spectralism

I realized that a possible solution could be the systematization of the Persian dastgāh micro-intervals through spectralism. I tried to match the notes and ratios resulting from the harmonic series to dastgāh music in order to find the precise tones and tunings that fitted the Persian maqām microtones and micro-intervals.

Spectralism focuses on the phenomenon and acoustics of sound, rather than its potential semantic quality. Step materials and interval content are often derived from harmonic series, including the use of microtones and, mostly, the verticalization of sounds. Spectral analysis of acoustic sources is used as inspiration for orchestration as well. Reconstruction of electroacoustic source materials using acoustic instruments is another common approach to spectral orchestration.

With the help of analyses and studies of spectral analysis software, composers of spectral music, such as Gerard Grisey and Tristan Murail, have explored the possibilities available in a single sound. They used harmonics as the primary source for their compositions, and often designed the metric, rhythmic, and even orchestration space of their works from it.

Harmonic Series

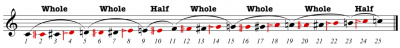

A harmonic series, or overtone series, is the sequence of harmonics, musical tones, or pure tones whose frequency is an integer multiple of a fundamental frequency.

A musical instrument is the acoustic amplification of a string or column that oscillates in different positions simultaneously. At the junctions of any state of vibration, when they move in either direction along a string or column of air, a combination of them amplifies and neutralizes to form a static or standing wave.

We know that if the length of a string is halved, assuming the other characteristics are constant, the frequency produced by it doubles. If the length of the string becomes a third of the original, its frequency will triple, and so on. To get harmonics, it is enough to divide the length of the main string into smaller pieces, so we place the fixed vault (bridge) in the middle of the string. This vault has halved the length of the string, so the resulting note will be doubled in frequency and the resulting harmonic will be produced; that is, the resulting note will sound one octave higher than the original note. On the smaller side of the string, which is a third of the length of the main string, the frequency is three times the frequency of the main note, and produces the third harmonic. The resulting note will sound exactly one octave and a perfect fifth above the original note.

Using these special components of the harmonic series as the basic material of composition, a distinctive expression in spectral music can be achieved. These tones, which are components of Iranian instrumental music, can be spread in color-harmonic textures and used in a spectral effect.

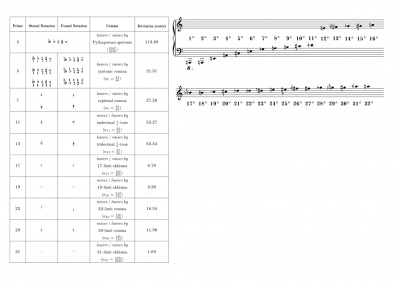

The Helmholtz-Ellis Notational System

During my attendance in Marc Sabat’s course in microtonal composition at the UDK Institute for Microtonal Music in Berlin, I was very much inspired by his innovative Microtonal Notation System called Helmholtz-Ellis Just Intonation (HEJI). HEJI is based on the Helmholtz-Ellis microtonal accidentals and extended by Marc Sabat. The extended just intonation pitch notation was devised for the composition and performance of new music using the sonorities of just intonation2 and the harmonic series.

Because Persian dastgāh music is mostly tuned by ear, the HEJI notational system is most fitted to calculating and notating Persian micro-intervals. Thus, Persian scales can be used as a tool for composing music. It also enables the exact notation of all intervals that may be tuned directly by ear.

My Compositional Thinking: «Micro-Moments VII»

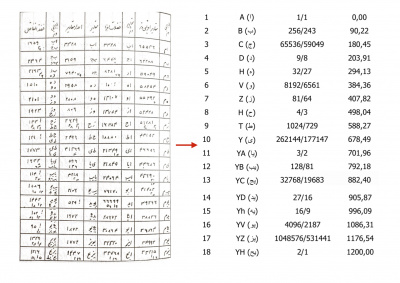

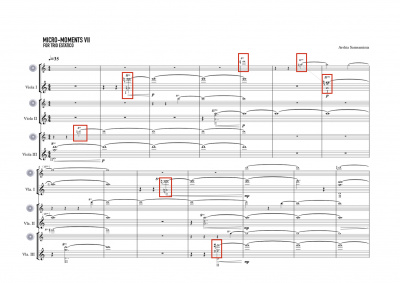

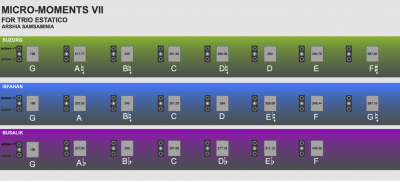

«Micro-Moments VII» is part of a composition cycle Micro-Moments which relates to my doctoral thesis. The idea is mainly to focus on Persian ancient micro-intervals and scales (dastgāh/maqām) using the HEJI notational system. At the foundation of «Micro-Moments VII» are three maqāms (buzurg, isfahan, busalik: see score below), recalculated from the book Jameh-al-alhan written in the 13th century by the Persian philosopher and theorist Abd al-Qadir al-Maraghi.

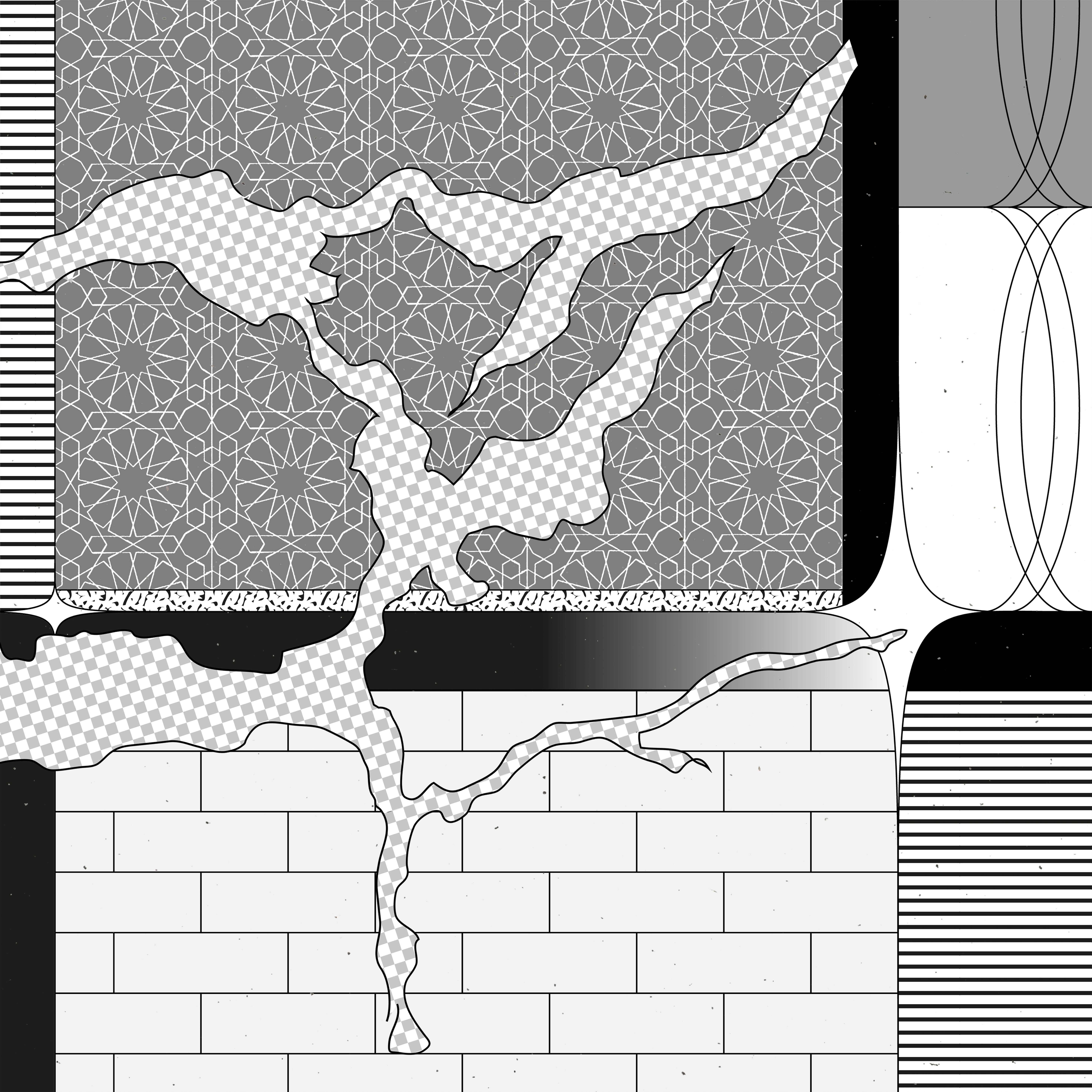

The standout features I use in my compositions are scordatura (open strings harmonics whether natural or pressed), fingerings and lip positions for the wind instruments, and electronics as a medium to assist with intonation cues to the performers. The picture below shows the mixing of the three maqāms, using the HEJI system for its notation for three violas and three Bluetooth speakers.

In order to help the performers to find the correct pitches based on the calculated scales and tones, I designed a tuning patch as a tuning tool for each piece and I shared it with the performers as a supplement to their parts. In addition, software like Spear, Scala, and Max for Live need to be considered as a necessary tool for processing frequencies and analyzing the sounds through the spectrograms in order to calculate the most appropriate micro-intervals, partial numbers, and ratios of the microtones to make dastgāh more applicable for the performers and more practical for composers to use as a raw material for composing in any styles.

I believe that systemizing Persian music using the HEJI notation system and calculations makes Persian music performable for different musicians with various cultural backgrounds. Also, it would be an influential cultural step toward introducing the potential of Persian music and its micro-intervals to other musicians, performers, and composers around the world.

List of References

This text is peer reviewed by an academic professional (single blind peer review).

This text is part of the Norient Special «Klangteppich: Voices from the Iranian Diaspora and Beyond», published in the run-up to «Klangteppich: Festival for music of the Iranian diaspora IV». The Special was curated and edited by Franziska Buhre. More on the projects and artists can be found here.

Klangteppich IV is funded by the Kulturstiftung des Bundes (German Federal Cultural Foundation). Funded by the Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien (Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media) and the Co-Financing Fund Berlin.

Biography

Shop

Published on May 19, 2022

Last updated on April 30, 2024

Topics

Special

Snap