Sonic Alterity – Race, Orientalism, and Popular Music

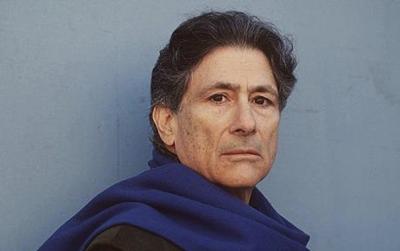

The second part of Norient's dossier «Popular Orientalism(s)» extends Edward W. Saids discourse on the appropriation of the Orient by white musicians such as Dschingis Khan, German language R&B, Lady Gaga and M.I.A. In the interview with Anta Helena Recke, Alexander G. Weheliye speaks about Said's dissociation from Black Studies and feminism, the iconography of the exotic and the foreign, hip hop hypermodernity and how the Orient is feminized in the western perception. The interview is based on a lecture, Weheliye held at the institute for music and musicology, University of Hildesheim as part of the symposium «Popular Orientalism(s)».

[Anta Helena Recke]: How are race and racisms defined in Said’s theorization of Orientalism and how do you see it?

[Alexander G. Weheliye]: Although Said presents Orientalism as a form of racism, he distinguishes it very clearly from «proper racism». When Said does mention racism in Orientalism and Culture and Imperialism, it is usually in the form of a virulent and hostile racial antagonism. The main problem is that Said does not theorize race or racism in any sustained manner, which leaves the door open for the naturalization of race/racism because they are assumed to simply exist, rather than being a product of massive amounts of legal, scientific, political, economic, cultural, discourses and institutions. My questions: How is Orientalism itself a mode of producing race and racial hierarchies? How does Orientalism differ from anti-black racism? One of the places where Said articulates this most clearly is in a 1985 essay «Orientalism Reconsidered», that responds to the many critiques of Orientalism from the perspective of minority discourses like feminism, Black studies, and ethnic studies. I shall quite consciously be alluding to similar issues raised by the experience of feminism or woman’s studies, black or ethnic studies, socialist and anti-imperialist studies, all of which take for their point of departure the right formerly un- or mis-represented human groups to speak for and represent themselves in domains defined, politically and intellectually, as normally excluding them, usurping their signifying and representing functions, overriding their historical reality. In short, «Orientalism Reconsidered» in this wider and libertarian optic entails nothing less than the creation of new objects for a new kind of knowledge (Said, 1985: 91).

[AHR]: Because he's so invested in western culture, Said distances himself from feminism, black studies, ethnic studies, etc. Why does Said feel the need to segregate himself from forms of discourse that enabled his path-breaking work in Orientalism in such a vehement manner when he writes the following lines?

[AGW]: But there remains this one problem haunting all intense, self-convicted, and local intellectual work, the problem of the division of labor, which is a necessary consequence of that reification and commodification. This is the problem for women’s studies: whether in identifying and working through any dominant critiques, subaltern groups – women’s, blacks and so on – can resolve the dilemma of autonomous fields of experience and knowledge that are created as a consequence. A double kind of possessive exclusivism could set in: the sense of being an excluding insider by virtue of experience (only woman can write for and about woman, and only literature that treats woman and Orientals well is good literature), and second, being an excluding insider by virtue of method (only Marxists, anti. Orientalists, feminists can write about economics, Orientalism, women’s literature) (Said 1985: 106).

Black and ethnic studies are not only institutional representations of minority-subjects in the US academy and negative critiques of the many different ways racial hierarchies structure western culture and society but are also invested in creating new modes of knowledge that make possible to view the world from non-hegemonic perspectives. Moreover, though the feminist and race theory based dismantling of racialized patriarchy paved the way for Said’s critique of Orientalism, he does not acknowledge how this intellectual labor contributes to his intellectual project. Said’s dissociating maneuver is not simply problematic because it mischaracterizes these important modes of inquiry and world-making, but also because it too easily conforms to the simplistic stereotypes that are brandished against any kind of work that speaks from a minoritarian perspective, especially in the United States (Schaefer Riley 2012). Why insist on the putative identitarian parochialism of minority discourse instead of its «creation of new objects for a new kind of knowledge», as Said states? That is, Said incorporates the insights of minority discourse while removing himself its local color, if you will. Why the detachment from «local intellectual work»? Isn’t all intellectual work local, as Said shows so brilliantly in Orientalism, which has as one of its methodological goals to disclose the locality of the Occident, to discredit its avowed universality? In most of his work, even in Culture and Imperialism, Said sees himself not in conversation with Black studies or feminist theory but with European thinkers such as Auerbach, Foucault, and Gramsci. So thinking about this in more local terms, what is the relationship between Orientalism and racism? Isn’t Orientalism a form of racism?

[AHR]: What are allochronic technologies and how are they related to Popular music?

[AGW]: The idea of «allochronic» (allo: different chromos: time) is taken from anthropologist Johannes Fabian’s work, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (1983), in which he says that anthropological discourse works primarily by creating a dual structure that places non-western people in a radically different temporal space than western subjects. In this scenario the non-West must be both prior to and radically incommensurate with the imagined civilizational superiority of the West: the West and the Global South cannot exist on a coeval plane. In order for this mirage to work, though, many discursive and material frameworks are put in place so that the civilizational differences between the West and the non-West attain common-sensical truth-value. This what I mean by «allochronic technologies», which combine apparatuses, images, knowledges, sounds, and bodies to imagine a radically different temporal dimension for non-western and non-white people. Since the early part of the 20th century Popular music served as an important arena for creating and perpetuating this alterity. What are the particular allochronic technologies of western Popular music? How do they locate and spatialize black/brown bodies in a radically non-coeval temporality cum ontology, thus positioning these as not-quite-human or non-human within a framework of racializing modernity? How is this non-coevalness, of not inhabiting the same time (the «civilized» is in a different time than the «non-civilized») working within Popular music?

[AHR]: Where and in which forms can we find Orientalisms in German Popular music/ performance and what is specific about it?

[AGW]: Blackness and Orientalism were integral to the sound and visual iconography of eurodisco productions in Germany during the late 1970s and 1980s, usually in the form of sexualized exoticism. An example form the late 1970s is Dschingis Khan, almost all of their singles had some form of Orientalist theme: the group’s raison d’etre was to provide variations on Orientalism. Ironically – or not so ironically – what occurs in this moment of appropriation through dressing in vaguely «eastern» clothing tends to rearticulate the idea of foreignness, because it lives from the contradistinction of the white body (and that the body is white is important) and it’s adornment with materials that are supposedly not natural to it.

Dschingis Khan – «Hadschi Halef Omar»

Video not available anymore

Eurovision Song Contest 1979

Examples of black bodies, mostly black female bodies, deployed as harbingers of the exotic and foreign include the mock-Caribbean Fernweh-styling of The Goombay Dance Band and Boney M. In the case of Boney M. the actual vocals were sung by a white German producer, Frank Farian, but were visually performed by black bodies, something Farian would repeat with Milli Vanilli in the early 1990s.

Goombay Dance Band – «Sun of Jamaica» (1980)

As a result, the abstraction of Blackness and Orientalism from black and brown bodies tends to reinscribe this equation of Germaneness and whiteness. This continues the trend of white Germaneness trying to move beyond itself from the 1950s onwards in order to create white-German racial innocence in the aftermath of the Third Reich.

We see a different kind move in Turkish-German singer Muhabbet’s «Sie liegt in meinen Armen» (2005), who is the only practitioner of the genre R'n'Besk, a mixture of German language R&B and Turkish arabesque music. What is interesting about Muhabbet’s self-Orientalizing (a German-born singer who sings German language lyrics in a musical genre that is self-consciously «Oriental») is that it allows him to present a vulnerability in public that is usually not allowed for male performers of color and to claim Germanness through the performance. In order to occupy the space of hyphenated Germanness, however, Muhabett makes himself more Turkish in ways that a German audience is already familiar with.

[AHR]: How do Orientalism and gender and femininity correlate?

[AGW]: As Said and many other scholars of Orientalism have shown, there has been a long tradition of feminizing the Orient, and, I would add of Orientalizing femininity. Of course, there are differences between the two. More recently there have been many ways in which femininity has not only become synonymous with the Orient (think of the recent wars waged in the name of helping Muslim women, who, curiously enough, usually are not asked whether they would like to be saved by the West) but it has become one of the main strategies of describing and thinking about femininity, particularly in opposition to the lack of «proper femininity» in the West. The burqa and niqab are very much tied to and based in certain ideas of gender and Orientalism. In the West the burqa and niqab work as allochronic technologies of racialization, since they locate Muslim women and by extension all of the Middle East in an earlier, more unsophisticated time and space. In addition, this positioning also highlights how much more civilized and enlightened the western world is about gender equality than the «backwaters» of the Global South. As Jasbir Puar writes:

Veils have generated Orientalist fantasies of female submission, emerged as nodal fixation, been established as a standard topic of discussion in woman’s studies curriculum, and become an easy (allochronic) marker of an other (Muslim/Arab/Islamic) femininity – one of the most potent self/othering mechanisms in the history of western feminisms – (...) The burqa, the hijab and the headscarf, turbans mark gender (...) religion, and region, as well as signal, to the untrained eye, the most pernicious components of oppressive patriarchal backward cultures and traditions, those that have failed at modernity (2007, 181).

[AHR]: Lady Gaga and M.I.A. are both presenting themselves wearing a burqa/niqab. Why do you read this practice of cultural appropriation in two different ways?

[AGW]: A very recent example is Lady Gaga who has a track called «Burqa» on her last album, which is accompanied by the following image:

Lady Gaga has worn different types of burqas before, but the contrast between the luminosity of enlightened, western, sexually liberated, female whiteness and the backwards, retrograde, and premodern burqa in these images is quite remarkable. As opposed to the luminosity of Lady Gaga’s phenotypical whiteness, in her 2013 video «Bring the Noize» M.I.A. uses the radiance of white clothing on black and brown bodies, including her own, as a decolonial critique of allochronic discourse and a celebration of bodies of color in hip-hop modernity, a modernity that has enabled the appearance of a figure such as M.I.A.

M.I.A – «Bring the Noize»

M.I.A. has also frequently worn a niqab, usually adorned with images. Another example can be found in the photo that shows M.I.A. donning a niqab adorned with Scarlett Johansen’s face. She takes on another form of luminous whiteness than Gaga: Scarlet Johansson’s face, who is considered to be one of the most beautiful women in Hollywood, to highlight the allochronic way in which the niqab has been used in the West.

White bodies signify differently in the racial regime than brown bodies. Also, M.I.A. using niqab with white faces, redeploying Orientalist discourses given that terrorism and veiling are already projected onto M.I.A.'s brown, female body. So it's a different form of appropriation, since Lady Gaga's use of the burqa simply reinscribes allochronic positioning of non-western others. What is important here is the luminosity of her whiteness, of Gaga's white skin, especially if we think about how Gaga's paleness is so central to her public persona in comparison to other contemporary female pop stars. Lady Gaga's whiteness represents an insurance policy that guarantees that her deployment of the burqa is not read as an Orientalizing allochronic technology but as a civilized feminist critique of the backwardness of these practices.

[AHR]: Concerning Orientalism and racialization what is specific about M.I.A.’s work?

[AGW]: M.I.A infuses her artistic practice with sights, sounds and politics from the Global South, especially the «Orient», deploying these not as fountains of premodern authenticity but as thoroughly ensnared in the planetary technological flows of bodies, capital and ideas. The entanglements between «the West and the rest» become perceptible in M.I.A.’s work via the mixological juxtaposition of putatively incongruent components and by Orientalizing the West. What M.I.A. has done is to bring these different sounds from the Global South into the language of western hip-hop. M.I.A never uses these sounds and images as ethnographic exhibits of an earlier, allochronic moment but accents the hyper-modernity, the hip-hop modernity of these sounds. M.I.A creates sonic and visual templates that bring all these things together and never hides the sutures. She plays with clothing, adornment, veiling, unveiling, terrorism, and so on, as well as ideas about gender and race.

M.I.A – «Bad Girls» (2012)

With this video M.I.A. was accused of many things including cultural appropriation because she is not from Saudi Arabia. Nevertheless, I really want to take seriously the idea of hip-hop-modernity that puts all these different signs: the gold-chains, the cars, a particular type of dancing, the veiling, and the horse at the level of material and textual surface, staging Orientalism as a clashing pop spectacle that messes with these signifiers for «backwardness» and instead shines a spotlight on their fabulous hip-hop-ness. In that way, the video coupled with the song is much more than a mere critique of Western Orientalist discourses, because it actually allows us to see how these subjects and objects usually function as temporalized signs for racial difference via the conduit of locating non-white bodies and their cultural accouterments in a different time and place, which, as a result, excludes them from what it means to be properly human in the West.

[AHR]: Are there other examples on the same level of popularity?

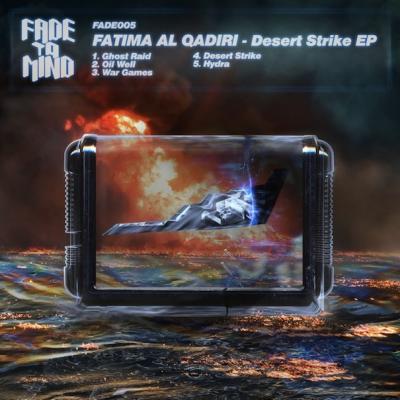

[AGW]: Not really, at least not in the Anglophone world. Though some musicians, who are further removed from the mainstream than M.I.A. have taken on the othering mechanisms of western popular culture, for instance, the Kuwaiti-American musician, Fatima Al Qadiri, who based her EP Desert Strike on the video game:

Desert Strike – «Return to the Gulf» (1992)

Al Qadiri is also a member of electronic music «super group» Future Brown, and the cover for her forthcoming album, Asiatisch, plays with the conflation of the Orient and femininity.

Another example is recent the collaboration, «Indians From All Directions», between Canadian Indigenous group, A Tribe Called Red, and Das Racist, a NYC hip-hop group consisting of members South Asian and Latino heritage, which critiques the colonial conflation between indigenous subjects in the western hemisphere and those hailing from India.

A Tribe Called Red & Das Racist – «Indians From All Directions»

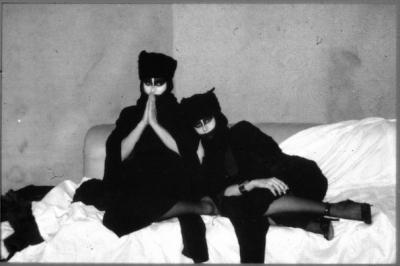

[AHR]: In this example of the German Band Saâda Bonaire (early 1980’s), the English vocals with that dominant German accent, do you see more the M.I.A. or the Dschingis Khan self-Orientalizing-strategy? How could the burqa-wearing performers be read in these pictures?

Saâda Bonaire – «You could be more as you are»

Actually the members of Saâda Bonaire are not wearing burqas/niqabs but what looks like Tuareg clothing coupled with make-up vaguely reminiscent of Japanese Kabuki Theater. In terms of Saâda Bonaire’s music, the group use «Oriental» sounding guitars coupled with stereotypically Germanic voices, highlighting – though more «artistic» and «serious» than Dschingis Khan – once again the necessary schism between the whiteness, Germanness, and femininity of the performing body and the perceived exoticism of the clothing and music. Saâda Bonaire are also part of the post-punk turn to «non-western and Black western musics» as resources in order to move beyond the musical limitations of punk rock, as was the case with David Byrne’s and Brian Eno’s highly influential 1981 album My Life in the Bush of Ghosts.

David Byrne/Brian Eno – «My Life in the Bush of Ghosts»

Video not available anymore.

We can also see these strategies of self-othering in the German group, Liaisons Dangereuses, whose 1981 track «Los Niños Del Parque» influenced early practitioners of Chicago house and Detroit techno in the United States:

Liaisons Dangereuses – «Los Niños Del Parque»

Quellenverzeichnis

Biography

Published on May 16, 2014

Last updated on July 27, 2020

Topics

From Beyoncés colonial stagings in mainstream pop to the ethical problems of Western people «documenting» non-Western cultures.

About Indian musicians in German pedestrian zones and the relationshis of music and place in academic research.

Why is a female Black Brazilian MC from a favela frightening the middle class? Is the reggaeton dance «perreo» misogynist or a symbol of female empowerment?

How artistis deal with this non-natural but political category as a result of its ideological dominance.